Carnivorous Plant Keeps House With Ants

A diving ant walks along the tendril of a pitcher plant in Borneo.

Deep in a forest on the island of Borneo (map), an ant wanders around on a carnivorous plant, seemingly courting a grisly death. But new research shows that the diving ant (Camponotus schmitzi) has nothing to fear from the fanged pitcher plant (Nepenthes bicalcarata), because the two organisms need each other alive.

Mutualistic relationships between insects and plants are nothing new: Some insects guard their plant hosts against herbivores, while others bring in nutrients that would otherwise be unavailable to the plant. The insects get a ready source of nectar and a place to live.

But this most recent find, published May 22 in the journal PLoS ONE, solves the mystery of a relationship that seems one-sided on the surface. It turns out that the ant keeps a precious nutrient—nitrogen—from leaving the pitcher plant.

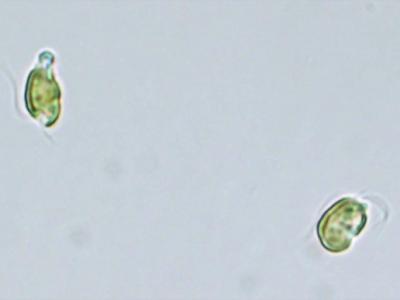

Pitcher plants have jug-shaped leaves filled with digestive juices. Insects that get too close to the edge and slip in are then slowly dissolved and digested in the fluid. But diving ants have no problem going in after these unfortunate souls and consuming the drowned insects, thereby stealing the plant's meal.

But rather than trying to rid themselves of these interlopers, the fanged pitcher plant actually houses diving ant colonies.

"[That] is generally an indication that the ants give [the plant] some benefit," said Judith Bronstein, an evolutionary ecologist at the University of Arizona in Tuscon, who was not involved in the study.

"But it's always been a mystery what the benefit is," she explained.

Something for Nothing?

Fanged pitcher plants with diving ant colonies grow more quickly than pitcher plants without the ants present, the study authors write.

But no one has been able to satisfactorily explain why the ants and the pitcher plants cooperate, said Mathias Scharmann, an ecologist who performed the study while at Cambridge University in England.

So Scharmann and his colleagues set out to see if the ants were enhancing the plant's nutrients, and if so, how.

The scientists used a form of nitrogen—a precious and limited nutrient for the pitcher plant—and traced its path from the diving ants to their plant host.

It turned out that when the diving ants excreted their waste or died, the pitcher plants absorbed the nitrogen contained in the feces and carcasses.

No Escape

But diving ants aren't the only insects that use the fanged pitcher plant. Flies and mosquitoes lay their eggs in the pitcher-shaped leaves, and their larvae also feed on the drowned insects. Once the larvae metamorphose into adults, they fly away, removing nutrients that could have gone to the pitcher plant.

Diving ants prey on these larvae, ultimately allowing the pitcher plant to keep their precious load of nitrogen.

If all of the fly and mosquito larvae never escaped the pitcher plant, the plant would have about 19 percent more nitrogen available, said study author Scharmann.

"It's a very elegant study," said Brigitte Marazzi, a botanist at the National Council for Science and Technology (CONICET) in Argentina and a former National Geographic grantee.

No one was able to demonstrate what the nutrient path from the ant to the plant looked like until now, explained Marazzi, who was not involved in the study.

Bronstein agrees, saying that the study authors' explanation as to why the diving ants and the fanged pitcher plants cooperated was pretty convincing.

"The insects that the ants are mostly eating are insects that have the ability to escape the pitcher plants," Bronstein said. "So the ants are keeping the nutrients in the plants that would otherwise be lost."

"This is a great example of why you wouldn't be able to understand [a relationship like] this if you only took two species into account," she said. Had the study authors only looked at the pitcher plant and the diving ant, they might have missed what was going on with the fly and mosquito larvae, Bronstein added.(Jane J. Lee,National Geographic,Published May 22, 2013)