Curiosity to Help Europe's ExoMars Zero-in on Life

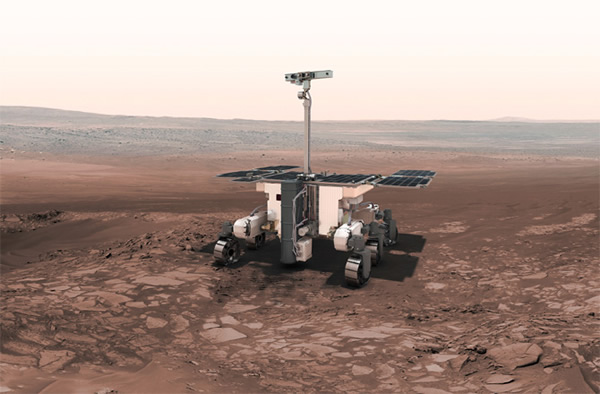

Artist's impression of the European ExoMars rover exploring the Martian surface.

A self-portrait of NASA's Mars rover Curiosity combines dozens of exposures taken by the rover's Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) during the 177th Martian day, or sol, of Curiosity's work on Mars (Feb. 3, 2013) at the "John Klein" drill site.

Scientists this week began assessing what may be the most important part of an upcoming mission to look for life on Mars: location, location, location.

Europe’s ExoMars rover, slated for launch in 2018, will be the most focused and ambitious attempt to find evidence of past or present life on Mars since NASA’s Viking expeditions four decades ago.

ExoMars’ planners aren’t starting from scratch, however. Recent findings from NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity mission, for example, indicate that ExoMars may not have drill down very deep -- or perhaps not at all -- to collect viable samples for analysis.

ExoMars will carry a drill capable of burrowing up to 6.6 feet (2 meters) into the planet’s surface. Scientists figure that at that depth, organic materials -- if they exist -- would be shielded from the onslaught of damaging radiation that constantly pummels the planet.

“One of the things that Curiosity has been able to do is understand that not all surfaces on Mars are created equal and have equal ages,” California Institute of Technology geologist John Grotzinger, who leads the rover’s science team, told Discovery News.

Last year, researchers discovered that Mars’ winds sometimes do the digging for them, exposing relatively fresh rocks at the base of scarps.

“One result from MSL that may be useful is that the depth (to collect samples) maybe less than 2 meters,” ExoMars project manager Vincenzo Giorgio told Discovery News. “We can definitely accommodate that.”

“If it turns out that drilling is complicated and inefficient, you can save that capability for when you need it the most,” Grotzinger added.

Unlike ExoMars, Curiosity was not designed to look for life directly. Instead, it is assessing if a region of Mars, known as Gale Crater, has or ever had the necessary ingredients and environments to support life.

Within months of Curiosity’s August 2012 landing, scientists learned that the answer was “Yes.” The rover now is on its way to assess the habitability of other sites and figure out how any organic material could have been preserved.

Even if life never took hold on Mars, the planet should have a rich stew of organic material from crashing comets and asteroids.

By the time ExoMars managers choose a landing site in 2016 or 2017, they may have even more guidance from Curiosity.

“We’re not just after water anymore,” Grotzinger said. “Now we’re honing in on the right kind of habitable environments. Then, we have to have (the right instruments) to know which subset of those habitable environments might contain the organic goodies.

“I think each time we do this, we’re getting more sophisticated. We’re getting a better understanding. But it’s also a much tougher question each time,” Grotzinger said.

In addition to data from Curiosity, sister rovers Opportunity and Spirit, and past landers, scientists will use imagery and chemical analysis from Europe’s Mars Express, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and other Mars-orbiting satellites to assess prospective landing sites for ExoMars.

Scientists met in Madrid this week to begin considering eight potential landing sites, all near Mars’ equator. They hope to winnow the candidates’ list to four by June or July.(Mar 28, 2014 05:40 PM ET // by Irene Klotz)