Civil War Shipwreck Revealed by Sonar

Time Capsule

New 3-D images (bottom picture) released today by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) show the Civil War-era gunboat U.S.S Hatteras (top) in exquisite detail.

Severe storms, such as 2008's Hurricane Ike, have moved sand off of the shipwreck that sank during a battle exactly 150 years ago, on January 11, 1863.

Resting in 57 feet (17 meters) of water, the shifting sands enabled archaeologists to go in with high-resolution sonars and map newly uncovered parts of the wreck.

The resolution is so good, "it's almost photographic," said archaeologist James Delgado, director of maritime heritage for NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. Delgado and his collaborators have also produced fly-through animations of the historic site and war grave.

"You literally are giving people virtual access to the incredible museum that sits at the bottom of the sea," he said.

—Jane J. Lee

Outgunned

On this day 150 years ago, the Hatteras, under the command of Hommer Blake, tried to prevent a Confederate commerce raider, the Alabama, from running a blockade set up around the port of Galveston, Texas (map).

Woefully outgunned—as shown in the above painting, "The Fatal Chase"—the Hatteras was blown full of holes and sank to the bottom, taking two men in the engine room with her.

Archived documents state that the two crew members who died were Irish immigrants, Delgado said. They may have joined the U.S. Navy to gain citizenship, or to escape harsh economic times, he speculated.

"And they paid the full measure for their service. Did they set out to die in a burning, steam-filled engine room? No, but they stayed at their station."

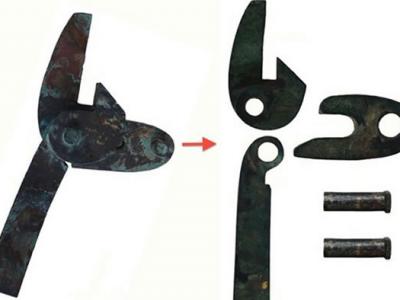

Steam Power

Part of the steam cylinders (pictured in a closeup) that powered the Hatteras' paddle wheels has started poking above the sand.

Built in Wilmington, Delaware (map), and launched in 1861, the ship was originally christened the St. Mary. President Lincoln had recently established a blockade of U.S. ports, but the Navy did not have enough ships to enforce it, said Delgado.

So they immediately purchased the St. Mary, retrofitted her as a gunboat, renamed her the U.S.S. Hatteras, and sent her to Florida for blockade duty.

Starboard Paddle Wheel

From Florida, the Hatteras used her paddle wheels—the starboard one is pictured above—to take her Navy crew to Galveston, which had been retaken by Confederate forces.

They were about 20 miles (32 kilometers) off the coast of Galveston when it started getting dark, said Delgado. The crew saw a steamship approaching and hailed her.

The approaching crew initially identified their ship as the H.M.S. Petrel, said Delgado. As the Hatteras lowered a boat into the water for their crew members to investigate, the men aboard the Petrel then identified her as the Alabama and opened fire on the Hatteras.

Full of Holes

The new, high-resolution sonar images enabled Delgado and collaborators to pick up details on the wreckage, such as damage to machinery in the engine room (pictured, the steam cylinders) that scientists hadn't known about before.

"[The] Alabama had been built in England as a warship for the Confederacy," said Delgado. "For 13 minutes the two ships traded gunfire, but the Hatteras was outgunned, shot full of holes, and sank."

Wheels Go Round

Their sonar scans also recorded a bend in a shaft connected to one of the paddle wheels (pictured, the starboard paddle wheel), indicating it was damaged when the ship capsized, according to a NOAA statement.

"What I think was exceptional was the captain and his men knew they were outgunned, but they went in anyway," Delgado said.

Watery Grave

A top view of the Hatteras shows its paddle wheel at the top and its steam cylinder near the bottom.

Just as new sections of the ship emerge from the seafloor, this mapping project has given Delgado the opportunity to dig through archived documents to discover stories about the men aboard the doomed gunboat.

Two of the bravest men, according to the captain, were stewards who went above and beyond the call of duty, said Delgado.

When one of them saw that a fire was heading toward the munitions, he tried putting it out while also throwing ammunition up to the men on deck. Delgado noted that the other steward took up a rifle and kept firing on the Alabama.

Past and Present

A fishing net, likely only decades old, drapes over machinery that once connected the Hatteras' pistons to its paddle wheels, said Delgado.

From archived documents, the NOAA archaeologist learned that Blake, the ship's commander, surrendered as his ship was sinking. "It was listing to port, [or the left]," Delgado said. The Alabama took the wounded and the rest of the crew and put them in irons.

The officers were allowed to keep their swords and wander the deck as long as they promised not to lead an uprising against the Alabama's crew, he added.

From there, the Alabama dropped off their captives in Jamaica, leaving them to make their own way back to the U.S.

Delgado wants to dig even further into the crew of the Hatteras. He'd like see if members of the public recognize any of the names on his list of crew members and can give him background on the men.

"That's why I do archaeology," he said.