Canal Linking Ancient Egypt Quarry to Nile Found

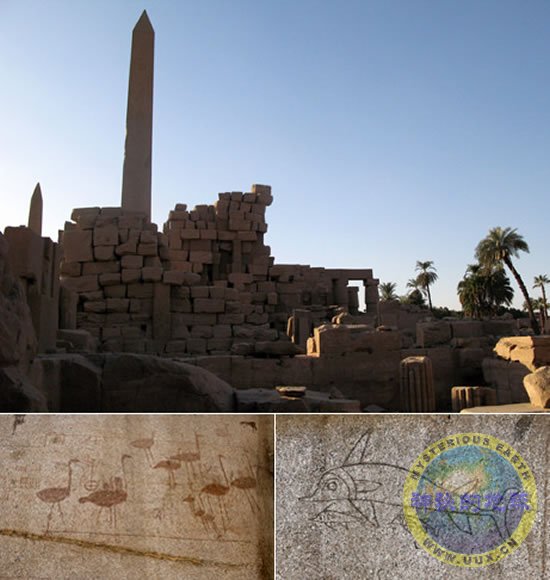

Experts have discovered a canal at an Aswan rock quarry that they believe was used to help float some of ancient Egypt's largest stone monuments to the Nile River. Most ancient Egyptian stonework, like the obelisk erected by Hatshepsut seen here (top), was quarried and shaped in Aswan.

The discovery is the first concrete evidence for a long-held theory that ancient workers transported their massive stone monuments directly by water.

Now scientists are concerned that saltwater corrosion will destroy drawings of wading birds (bottom left), dolphins (bottom right), and other graffiti left behind by the workers.

Experts have discovered a canal at an Aswan rock quarry that they believe was used to help float some of ancient Egypt's largest stone monuments to the Nile River.

It has long been suspected that ancient workers moved the massive artifacts directly to their final destinations over waterways.

Ancient artwork shows Egyptians using boats or barges to move large monuments like obelisks and statues, and canals have also been discovered at the Giza pyramids and the Luxor Temple.

But the newfound canal, which has since been filled in, is the first proof discovered at the granite quarries in Aswan. Almost all obelisks, including those at the Luxor and Karnak Temples, were originally hewn in the Aswan area.

"What you have is very strong evidence that they may have loaded these stones in at the quarry ... and as a result not dragging and hauling them over land," said Richard R. Parizek, a professor of geology at Penn State University who led the scientific tests confirming the canal's existence.

"It eliminates that land connection."

Heavy Workload

Larger obelisks can weigh more than 50 tons, said Adel Kelany, an inspector with Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities who led the team that first dug up the site in 2002.

And a well-known unfinished obelisk at the quarry is thought to weigh more than 1,100 tons. It was the largest such monument ever attempted but was abandoned after latent cracks emerged, revealing a rare glimpse of ancient construction practices.

"We have actually long suspected the existence of a canal linking the Nile to the quarry site, and it's very nice to find this real confirmation," said Salima Ikram, an Egyptologist at the American University of Cairo.

"If they had just been using rollers and dragging things each time, everything would have been much more time-consuming and far slower."

Experts said the canal likely filled in with water during the one of the Nile's annual floods. Workers would have dragged the large stone monuments onto rafts at a point below the floodwater level, allowing the artifacts to float when the water level rose.

The canal was probably a natural split in the quarry granite, exploited and shaped by workers to make it more functional, the scientists added. Geologists found tooling marks along the canal similar to those where obelisks were removed.

The findings were announced at the Second International Conference on Geology of the Tethyr at Cairo University in March and will be published in advance of the next meeting in January.

Tourists and Trenches

Kelany and his team first were prepping the area for tourists in 2002 when they discovered a small trench about 27 feet (8.25 meters) deep and 8.2 feet (2.5 meters) wide at its narrowest point in an otherwise flat area of solid granite.

The workers suspected the trench was part of a larger canal or harboring area. But digging was forced to halt when the excavation hit groundwater, and much of the site was then backfilled with gravel for safety reasons.

"We were unable to remove the water from the canal, and if we left it like that it would be quite dangerous for a tourist site," Kelany said. "The water would not move, and it will not change ... it would have bacteria."

The site was left untouched until 2004, when a team of scientists set out to verify the canal's existence through a series of less invasive scientific tests.

Mapping the Canal

The researchers used shallow seismic surveys to test for variations in the area's topography by sending energy into the ground along lines that were at right angles to where the canal was thought to be.

The team also tested the underground temperature, thinking the area of the canal depression would be cooler due to the presence of groundwater.

"Both techniques showed that this anomaly did exist—it did go beyond what was previously excavated," study leader Parizek said.

Scientists were able to map about 456 feet (139 meters) of the canal but could not go farther because the site runs into a modern highway and then an Islamic cemetery.

But the site is roughly 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) from the Nile gorge, and scientists believe the canal becomes wider and deeper before possibly linking up with a main channel.

Salty Dilemma

Along with the discovery of the canal, the archaeologists also turned up ancient graffiti left behind by quarry workers and gridlines used in the obelisk-sculpting process.

The depictions, which include images of dolphins and ostriches, are now endangered by rising water levels and an accumulation of salts, according to experts.

Many sites in Egypt have been threatened by salt deposits since the building of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s, which prevents the Nile from flooding each year and washing away the minerals.

"Generally, Egypt has always been salty because of course it used to be under the ocean," said Ikram, the Egyptologist.

"When the Aswan Dam was built ... the regular washing out of the salt from the land also ceased and therefore the overall problem in Egypt is destruction by salt."

The dilemma is magnified in part by the gravel used to fill in the original excavation site. The rubble allows groundwater to rise to the level of the drawings, which were left uncovered.

Granite, a porous rock, is not normally affected by water infiltration as much as other rocks like limestone.

In this case, however, "the capillary moisture is coming back out of the gravel since they backfilled the excavation," Parizek said.

Scientists have proposed various solutions to stem the water flow. A clay barrier, for instance, could dam the previously excavated area and allow experts to pump out the existing water.

"It's just falling into ruin," Parizek said. "There are artifacts there that are so unique that it would be a crime to lose them."