Prehistoric Shark Nursery Found at Illinois Nuke Plant

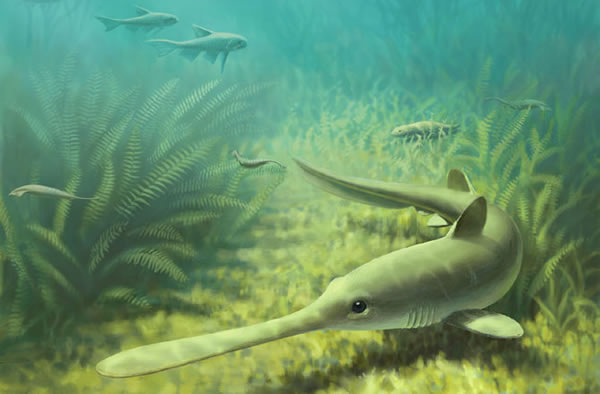

This long-snouted shark called Bandringa was one of the earliest close relatives of all modern sharks.

The earliest shark nursery containing fossils of both young sharks and eggs has been found at the site of a nuclear power plant in northeastern Illinois.

The nursery, once located at what is now Mazon Creek at the Braidwood Nuclear Generating Station site, dates to 310 million years ago, according to a paper published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. It used to be teeming with a long-snouted shark called Bandringa, which was one of the earliest close relatives of all modern sharks.

"At least a dozen juvenile Bandringa shark fossils -- and probably more -- have been recovered from the site," University of Michigan paleontologist Lauren Sallan, who co-authored the paper with Michael Coates, told Discovery News.

Some of the fossils are in a remarkable state of preservation.

"We even have soft body tissue from the juvenile sharks," Sallan said, adding that the tissue retains pigment that, in the future, could reveal the precise coloration of the sharks. DNA could probably not be extracted from it, though.

The paleontologists studied the fossils, along with those of 12 adult Bandringas. This shark was previously classified into two species, but the researchers determined that all of the fossils belonged to just one species. The scientists also gained a more complete picture of the extinct shark's anatomy and distinctive features.

"Bandringa had a head entirely covered in large spines, a long paddle-like rostrum (snout) with electroreceptors, and one of the earliest jaws capable of protruding and suction feeding," Sallan said.

It resembled present-day sawfish and paddlefish. The huge snout took up half of its body length. The electroreceptors on the snout helped the sharks to locate prey, which consisted of small crustaceans and other marine life.

Juveniles were 4 to 6 inches long. They grew into adults of up to 10 feet long.

The stomachs of some of the juvenile sharks even had tiny crustaceans still in them, indicating that these sharks died a sudden death before their meals digested. It remains a mystery for now as to what did them in.

Based on the location of the adult Bandringa sharks and the nursery, the researchers conclude that the adults migrated downstream from freshwater swamps in what are now Pennsylvania and Ohio to a tropical coastline to spawn. That prehistoric coastline is where the nuclear power plant now is.

The defined route marks the earliest known example of shark migration, according to Sallan and Coates. This early route additionally reveals the only known example of a freshwater to saltwater shark migration.

"It's also the earliest evidence for segregation, meaning that juveniles and adults were living in different locations, which (further) implies migration into and out of these nursery waters," Sallan said.

As to why sharks then, and now, rely upon nurseries, she explained that the more isolated regions chosen for nurseries protect juveniles from larger sharks and other potential predators.

The gestation period for sharks can also be quite long -- up to two years -- making the protection all the more important.

Paleontologist John Maisey of the American Museum of Natural History told Discovery News, "The paper offers some interesting speculation about breeding behavior, based upon a literal interpretation of the fossil distributions -- adults in one place, babies and eggs in another."

Maisey, however, said that it is challenging to infer how such ancient species behaved based on tangible evidence.

He explained, "Behavior does not readily fossilize."(Jan 7, 2014 12:00 PM ET // by Jennifer Viegas)