ALMA: Extreme, Precision Astronomy in the Desert

The Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array, or ALMA, is already producing amazing science results. To see the telescope up close at an altitude of 16,500 feet (5,000 meters) is even more incredible. This high-precision instrument on top of the world is truly one of the most impressive sights that I have ever seen.

So what’s the big deal with a “millimeter and submillimeter” telescope anyway?

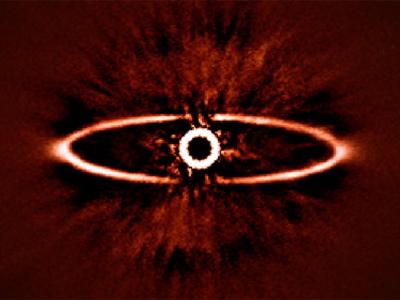

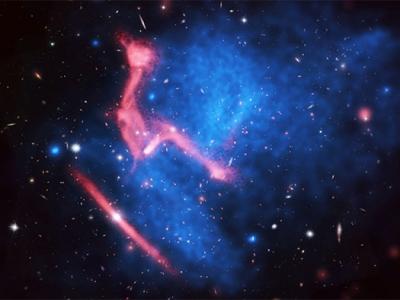

ALMA is the most sensitive instrument (by far) to probe this region of the electromagnetic spectrum just a bit longer in wavelength than infrared, yet still quite high energy for most radio astronomers.

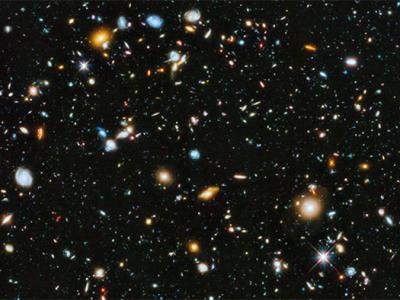

It has a special power to see an unbiased sample of the universe. That is, by a combination of an increase of star formation (and thus infrared emission) in the galaxies in the early universe and the way that light is redshifted by the expansion of the universe, you can see a whole swath of the history of galaxies in this band. However, it has traditionally been a difficult place to work since the water molecules in our atmosphere absorb and scatter much of the submillimeter light coming from space.

ALMA: Extreme, Precision Astronomy in the Desert

So, to some of the highest, driest mountain peaks we go.

I came to the Atacama Desert as a guest of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory along with several other science writers from around the United States. At the Operations Support Facility, located at an altitude of 9,500 feet (2,900 meters), we joined an even larger host of journalists from around the world to get a special tour of this remote facility.

The altitude was already wearing on a few of us that are used to sea level, especially when lugging around laptops and camera bags. We had a safety briefing before our trip to the high site where we were instructed on the use of our oxygen bottles and informed that a team of paramedics would be traveling with us to the high site, or Array Operations Site. This was about to get real.

Despite the occasional dizziness and mild headache once we reached the array, I actually jumped up and down and squealed with excitement upon seeing it in person. There were 54 dishes on site from North America, Europe, and East Asia, all built to the same precise performance specifications but each looking a little bit different. The surface accuracy of the gleaming 12-meter wide dishes is the width of a human hair, and the drives and motors that move them must point to an object with 0.6 arcseconds of accuracy. (That’s like pointing accurately at a single person in Charlottesville, Virginia, from St. Louis. Trust me, that’s a LONG drive.) Seeing the arrays in person was… beautiful.

That’s the other thing about observing in what we call “high frequencies” for radio astronomy. You are allowed a margin or error, but that is only a fraction of the wavelength of light that you are observing. Traditionally, surface and positions accuracies had to be good down to a centimeter, even a few millimeters. Very long wavelength projects can get away with even more, as I learned from my experience building telescopes that collected light with 2 meter wavelengths. (The very first array was more or less paced out. Seriously.) But with the short wavelengths viewed by ALMA, micron accuracy of the instruments must be achieved, and this is quite a technological hurdle.

The array even put on a bit of a show for us, slewing, or moving back and forth to point to different areas of the sky. At first, some of the moves were part of usual on-site testing, but then they really whirled them around for us to get video and pictures. I do not say “whirled” lightly as these dishes moved FAST. The 100-ton dishes can turn completely around in just a minute and do so extremely quietly.

Groups of eager journalists filed into a building to see the workhorse supercomputer called the correlator. It had been built in sections in Charlottesville, Virginia, and all connected at the array site by engineers, such as Alejandro Saez, who happily answered our questions. With a processing power of 3 million laptops, the correlator brings all of the antenna signals together from the 12-meter dishes so that a data product can be given to the astronomers. A second correlator is being built by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan to serve the 7-meter dishes in the center of the array that are there to image the most diffuse radio emission on the sky.

The excitement and jumping around continued until I was well out of breath, so I’d take a hit of oxygen every once in a while. I never did get my blood oxygen tested, but the paramedics noted that my pulse was a bit high. Others on site had a bit more trouble and were given tanks and nose plugs to help with the altitude sickness. These are also worn by staff who work at the high site, and they are restricted to only spending 6 hours a day there.

Back at the OSF, a few of us managed to get a tour of one of the labs where the electronics, or “guts” of the telescope are tested. I recognized the familiar blue drums of the cryostat that had been assembled in Charlottesville when I was a grad student, but the engineers had taken it apart so we could see inside.

The radio signals pass into the cryostat, cooled down to 4 Kelvin by liquid helium, and onto electronics that amplify the signal and change its frequency so that it can be handled by digital electronics. These amplifiers and receivers are what actually measure the amount (and phase) of radio light being collected by the telescope and are some of the most sophisticated in the world as they were designed specifically for this application.

My personal favorite device, however, was the robot arm that moves around in front of the receivers when the astronomer needs to calibrate the telescopes in order to make accurate measurements.

There is no doubt that I am a radio astronomy nerd. I’ve worked at several different observatories and delight in the mechanics of operation. However, this was a spectacle that wowed everyone in attendance. The technology, power, and raw human ingenuity and passion that go into such a project enough to move anyone to fall in love, as I finally did, with ALMA.

Mar 29, 2013 02:51 PM ET by Nicole Gugliucci