Scientists Link Extinctions, Rising Temperatures

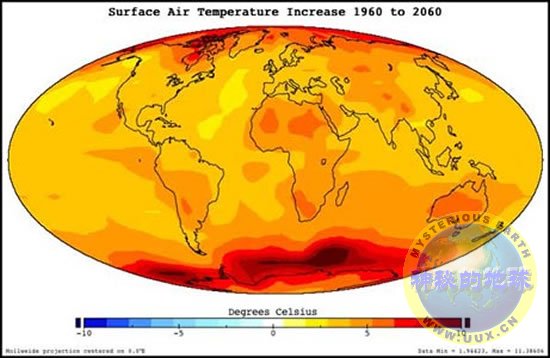

A NASA world map plots the annual average rise in surface air temperatures from 1960 to 2060 based on past measurements and future projections.

A new study suggests that within 200 years, Earth's temperatures may become hot enough to kill off half of all existing plant and animal species.

A team of British scientists contends that, within 200 years, Earth's temperatures may become hot enough to kill off half of all existing plant and animal species.

The researchers from the Universities of York and Leeds in Britain base that dire possibility on a new analysis of the 520-million-year-old fossil record, which links past mass extinctions with cycles of high temperatures.

"We could be in the temperature zone in which mass extinctions have occurred by the end of this century, [or] more likely in the next century," said Peter Mayhew, the study's co-author and an ecologist at the University of York.

A Strong Link

Benton and his colleagues lay out their findings in a paper that appeared in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Measuring in ten-million-year increments, the researchers found a correlation between high temperatures and four of five mass extinctions in Earth's fossil record.

No other research had examined both the entire globe and the entire fossil record, which begins about 540 million years ago. This analysis makes the strongest case yet for a solid link between temperature and changes in the number of species on Earth.

"There have been individual cases where people have shown that some kind of change is detrimental to certain groups," said Michael Foote, a paleontologist at the University of Chicago, who was not involved in the study. "But this is the first time anyone has studied the diversity of animals at a global scale and went back to estimates of temperature over time."

According to the research, Earth is in a process, millions of years long, of moving from colder to warmer temperatures—from the "icehouse phase" to the "greenhouse phase." The Earth will reach the peak of its latest warming phase in the next 60 million years.

It is possible that extinctions don't begin to occur until thousands, or even millions, of years after temperatures begin to rise. And the authors were careful to avoid claims about a causal relation between the rising temperatures and the extinctions.

Other things, such as cycles of cosmic rays from space or carbon dioxide levels, could also have played a role in the past mass extinctions.

Still, the authors say it may be possible to avoid some of the future extinctions if humans work to control temperatures.

"We don't want to over-extrapolate in our findings, but if they hold, it's quite a scary thing to contemplate," said Timothy Benton, a co-author and professor of population ecology at the University of Leeds.

Beyond the Paper?

The study resists speculation about the present phase of global warming or humankind's possible role in it. It also notes that periods when species died out were often followed by a stabilization—a time when new species would appear.

"You might make a case for the possibility that climate warming could lead to a smaller increase in diversity than you otherwise might have expected," Foote said. "But there was no clear evidence that it would lead to a decrease in diversity."

In interviews, both Mayhew and Benton went beyond the more cautious terms of their paper, saying man-made global warming was accelerating the process.

"The issue here is that we are creating the climate change, and we are creating the climate change at an unprecedented rate," said Benton. "So clearly we are creating the events for a climate-related mass extinction that wouldn't otherwise be happening."

Those statements echo other controversial ideas. The International Panel on Climate Change, which recently shared the (Nobel Peace Prize with former U.S. Vice President Al Gore, has warned of a possible drop in biodiversity if temperatures rise by three or four degrees.

And last year, experts from 13 countries wrote an article in the journal Nature saying that climate change could push 37 percent of all species to extinction within the next 50 years.

"We are on the verge of a major biodiversity crisis," that letter said. "Virtually all aspects of diversity are in steep decline and a large number of populations and species are likely to become extinct this century.

Other scientists contend that these ideas are flawed or exaggerated.

Richard A. Muller, a physics professor at the University of California, Berkeley, published a controversial piece in Nature in 2005 suggesting a link between changes in climate and changes in biodiversity.

He believes that global warming will devastate the environment, but stopped well short of linking human-made global warming to biodiversity loss. He also said Mayhew and Benton had gone beyond the science of their paper.

"You can't make wild predictions if you can't justify them," Muller said. "If global warming continues at the current pace, I think we will have a tragic future. I think there will be great disruption, but whether humans affect biodiversity in a negative way, I don't think anyone ever really knows."