Moonlet Study Sheds Light on Origins of Saturn's Rings

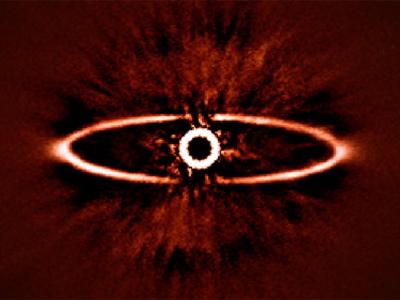

Saturn's rings are seen here in a panoramic mosaic of 165 images taken by the Cassini spacecraft. The color contrast has been greatly exaggerated to better show the color and size differences between the rings.

A new study found clusters of large ice chunks in the rings, lending support to the idea that the rings formed from moons that were slowly pulverized.

A new study of Saturn's striking rings has found clusters of "moonlets," lending support to the theory that large icy moons were slowly pulverized to form the ring system.

The boulder-size chunks, spotted in a narrow belt, could only have been formed when something collided into an object at least as large as Pan, Saturn's innermost moon, which is about 15 miles (25 kilometers) wide, scientists say.

The origin of Saturn's ring system remains a mystery. Some experts say the rings are remnants of the same gas and dust that formed Saturn.

Others support the idea that the ring's icy chunks formed from moons that were battered by asteroid impacts or blasted apart by collisions with meteors.

Unraveling the mystery of the rings' formation will help scientists better understand how our solar system—and alien ones—form.

"The origin and evolution of planetary rings is one of the prominent unsolved problems of planetary sciences," write the study authors in this week's issue of the journal Nature.

Encircled in Mystery

At ten times Earth's diameter, Saturn is the second-largest planet in the solar system.

Its rings are among the most beautiful features in the solar system: wide, flat discs of ice crystals that seem to float serenely in space.

The ice pieces range from the size of dust to more than ten feet (three meters) across.

For years researchers have noticed strange, paired bright streaks within Saturn's outermost ring, which is dubbed the A ring. The narrow band lies about 80,000 miles (130,000 kilometers) from the planet's surface.

Scientists call the streaks "propeller features," because they resemble the propellers of airplanes. Scientists now know that the features form when a larger object pushes debris into a wake, as if the moonlets were boats in water.

"These moons are not massive enough to make too much havoc in the rings, but they are still big enough to create some disturbance," said study co-author Miodrag Sremčević, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Colorado in Boulder. "It's like a mini-moon inside of the ring."

One prevailing theory has been that larger pieces formed when some of the smallest ice fragments came together over time. But the new study calls that into question.

Tumultuous Realm

Sremčević and his colleagues studied images captured by NASA's Cassini spacecraft in August 2005, when Saturn's rings were backlit by the sun.

The team found that eight of the moonlets in Saturn's A ring were concentrated in a narrow belt, not scattered throughout the ring like a peaceful origin would suggest.

All eight of the moonlets are between 160 and 500 feet (60 and 140 meters) across.

"I really did not expect that," Sremčević said. "I was thinking these moonlets are everywhere, and with more patience and observation we would find them throughout the rings."

The images instead suggest the rings are a tumultuous realm where massive collisions break apart football-field-sized ice chunks, and time grinds the pieces into ever smaller bits, kind of like how sand forms on Earth.

"Some bigger moon was orbiting within the ring and was struck by a larger meteorite or comet," Sremčević said. "What we see today are remnants of that larger moon."

Solar Clock

The boulders may be useful as a sort of clock to chronicle the rings' history, Sremčević said.

Particles larger than about 30 feet (10 meters) tend to get ground down over time by meteorite impacts and interactions with other particles in rings, he pointed out.

So it's possible that the larger the particle, the more recently it was formed, he added, though this idea needs to be tested a lot more.

Sremčević said a rough estimate for the timing of the collision that formed the eight moonlets is about a hundred million years ago.

Scientists have evidence that in 1984 a similarly catastrophic impact occurred when a three-foot (one meter) object slammed into an icy boulder of similar size in Saturn's inner D ring.

"We actually came up with one hypothesis that could match up everything," Sremčević said. "That was: the rings were created a long time ago. That's an old idea. These moonlets are younger than the rest of the rings."