Failure to Hunt Rabbits Part of Neanderthals' Demise?

Neanderthals did not learn how to hunt small animals such as rabbits (pictured, a group of animals Portugal).

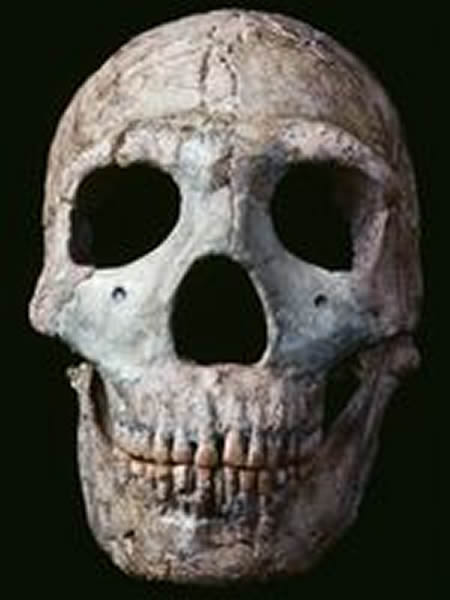

A Neanderthal skull from Wadi Amud, Israel. Photograph by Ira Block, National Geographic

Rabbits are small, fast, and devilishly hard to catch. And that could have had dire consequences for Neanderthals.

A new study suggests that an inability to shift from hunting large mammals to wild rabbits and other small game may have contributed to the downfall of European Neanderthals during the Middle Paleolithic period, about 30,000 years ago.

"There have been some studies that examined the importance of rabbit meat to hominins"—or early human ancestors—"but we give it a new twist," said study lead author John Fa, a biologist at the United Kingdom's Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust and Imperial College London.

"We show in our study that [modern humans] used rabbits extensively, but Neanderthals didn't."

Fa and his team analyzed animal bone remains spanning a period of 50,000 years from Neanderthal and modern-human-occupied sites across Iberia, the part of Europe that includes Spain and Portugal, and southern France.

They found that rabbit remains only started to became common at sites around 30,000 years ago, which is around the time that Neanderthals started to disappear and—perhaps not coincidentally—when modern humans first arrived in Europe.

The authors speculate that over the course of thousands of years, as climate change or human hunting pressure whittled down populations of Iberian large animals such as woolly mammoths, rabbits would have become an increasingly important food resource.

But Neanderthals may have been unable or unwilling to "prey shift" to smaller game, the authors argue in a new study, which will be published in an upcoming issue of the Journal of Human Evolution.

"Neanderthals were large mammals hunters, par excellence," Fa said, but they "could have found it difficult to hunt the smaller, but superabundant, rabbit."

John Shea, a paleoanthropologist at Stonybrook University in New York City who did was not involved in the research, agreed.

Most people underestimate how hard it is to hunt rabbits, Shea said. "If I say, 'Let's go hunt a mammoth,' you'll probably think I'm nuts and that we're going to die. But if I say, 'Let's go hunt rabbits,' then it's a piece of cake."

Weapons Not Up to the Task?

In reality, the cost and benefits for Neanderthals would have been almost reversed, Shea said.

"If you have the technology to kill a mammoth when you run into it"—as Neanderthals did—"then the risk is low and the return is high. Whereas with a rabbit, the cost in killing it is negligible, but the return is tiny."

The piercing spears and clubs known to have been used by European Neanderthals weren't very well suited for catching rabbits. In contrast, early modern humans used complex projectile weapons such as spear throwers and possibly bows and arrows—both of which are better for hunting small, fast-moving prey.

There are other ways to catch rabbits, however. There is evidence that Neanderthals were capable of making string, so it's very possible that they were able to weave nets and snares to use as traps, Shea said.

But even if Neanderthals could make such traps, they still might not have done so because of the high startup costs involved.

"There's more time and energy involved in trapping than most people think," Shea said. "You have to set a lot of them and monitor them, because once an animal is trapped, it becomes vulnerable to predation by rival carnivores."

The process could have been too demanding for Neanderthals, who likely had higher energy requirements than modern humans.

Stockier and more muscular than humans, and lacking humans' tailored clothes, scientists estimate that Neanderthals could have needed twice as many calories to survive and stay warm.

Bunny Hunting a Family Affair

Fa and his team speculate that most of the rabbit hunting among early modern humans may have been done by women and children, who could have stayed behind in settlements while the men went on hunting trips for larger prey.

The women and children "may have specialized in hunting rabbits, by surrounding warrens with nets or smoking the rabbits out of the warren," Fa said.

Ancient rabbit hunters may also have had help from a four-legged ally picked up during their travels from Africa: dogs.

The oldest fossil evidence for dogs is only about 12,000 years old, but there is genetic evidence suggesting dogs may have split from wolves as far back as 30,000 years ago-around the time that humans were arriving in Europe.

"What we are saying is that this may have occurred," Fa said. "The domestication of the dog for hunting purposes may have been a tremendous advantage for human hunters."

Why Not Adjust?

Bruce Hardy, an anthropologist at Ohio's Kenyon College, said he's unconvinced.

"I think the data is at a very gross level and they're drawing implications from it that are quite frankly speculative," said Hardy, who also did not participate in the research.

Hardy also finds it difficult to imagine that Neanderthals couldn't change their hunting strategies to target rabbits when they had thousands of years to do so, or turn to other food sources, such as plants.

"If they were this inflexible, why did they make it for 250,000 years?" Hardy said.

It's like saying "'Oh, the big animal are gone. I guess I'm going to starve now.' That doesn't make sense for any animal, not to mention a large-brained hominin that's very closely related to us."

But the Neanderthals' longevity might have been irreversibly tied to the big game they hunted, Fa said, and once those prey items disappeared, our highly specialized cousins found it difficult to adapt.

"We are not saying that small prey was not part of the diet," he said. "What we are saying is that the Neanderthals could have specialized to such an extent that [it] did not allow them to use a superabundant but more difficult to catch food source."

Ker Than

for National Geographic News

Published March 11, 2013