Beautiful Skull Spurs Debate on Human History

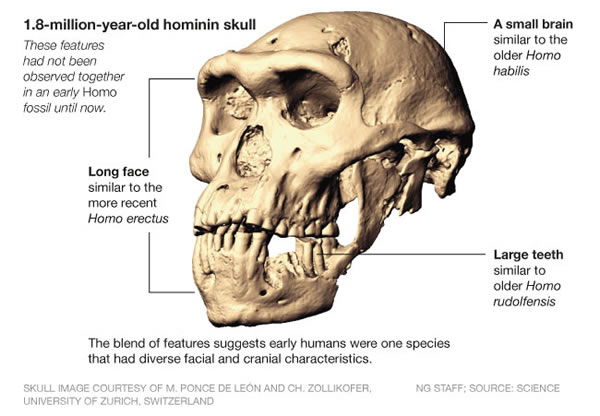

This skull's features resemble those of both earlier and later humans.

A newly discovered skull, some 1.8 million years old, has rekindled debate over the identity of humanity's ancient ancestors. Uncovered at the Dmanisi site in the Caucasus in Georgia, "Skull 5" represents the most complete jaw and cranium from a turning point in early human history.

Researchers, led by Georgian National Museum anthropologist David Lordkipanidze, first found the complete lower jaw of a fossil human in 2000. The cranium turned up five years later, at the fossil-rich Dmanisi site 96 miles southwest of Tbilisi, and is now being reported in the journal Science.

"It was discovered on August 5, 2005—in fact, on my birthday," Lordkipanidze says. He adds that the fossil's importance was clear as soon as the team saw it, but required eight years of preparatory analysis.

That is because Skull 5 is what paleoanthropologists often refer to as a "mosaic," or mixture of features seen in earlier and later humans. The skull's face, large teeth, and small brain size resemble those of earlier fossil humans, but the detailed anatomy of its braincase—which gives clues to the wiring of the brain—is similar to that of a more recent early human species called Homo erectus. This combination of features has fueled a long-running discussion over whether the Dmanisi humans were an early form of Homo erectus, a distinct species called Homo georgicus, or something else.

Dmanisi Fossil Trove

The newly described skull isn't the only one that has been found at Dmanisi. At least five relatively complete skulls have been found there in the last two decades. Those individuals may not have actually lived alongside each other, but apparently occupied this same place within a window of a few thousand years more than 1.75 million years ago.

Lordkipanidze and his coauthors suggest that, taken together, these skulls demonstrate how the Dmanisi humans varied in appearance from one individual to the next. "Together, our analyses suggest that Skull 5 and the other four early Homo [human] individuals from Dmanisi represent the full range of variation within a single species," study senior author Christoph Zollikofer of Switzerland's University of Zurich, said at a briefing on the new skull discovery.

Using morphometrics to gauge skull shape for each fossil skull, Lordkipanidze and colleagues found that the Dmanisi humans varied from each other in facial features and brain size, for example, about as much as modern humans do from each other. In other words, despite minor differences, they all belonged to the same species.

Family Tree Pruned

The single species finding raises wider implications for the history of humanity. Scholars have previously seen Dmanisi's inhabitants as a distinct variation of the human Homo erectus, or possibly as a new species. That would make them early emigrants out of Africa and part of a wildly branching early human family tree.

In the new study, however, Lordkipanidze and coauthors suggest that Dmanisi's inhabitants were actually part of a single human lineage that contains several earlier human species long thought of as distinct from Homo erectus.

So, who were the early humans living at Dmanisi? Lordkipanidze and colleagues place them in a single lineage of early humans that may stretch back as far as 2.4 million years ago in East Africa, when the first human species, Homo habilis, arose. This would lump the various human species that have been named during early Homo history into a single evolving species connecting Homo habilis to the Dmanisi humans, and forward in time to Homo erectus as it expanded across Eurasia. "We think that many African fossils can be lumped in this category and aligned with the single-lineage hypothesis," Lordkipanidze says.

Skull Skepticism

While other paleontologists recognize the fossilized beauty of Skull 5, not everyone agrees on the evolutionary assertions of the new paper.

"There's no doubt that this is an interesting cranium," says paleoanthropologist Bernard Wood of George Washington University in D.C. "It's a good playing card, added to some other playing cards that are equally good."

Anthropologist Fred Spoor of Germany's Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology agrees that Skull 5 is "an absolutely fabulous specimen." He says the skull will help researchers "figure out what's going on with the really early evolution of Homo erectus."

But both Wood and Spoor disagree with the "one big species" message of the new study.

The methodology used in the new study, Wood says, can obscure real differences between species, since the focus was on cranial shape rather than telltale anatomical features such as small openings on the skull for blood vessels or the delicate bony anatomy of the braincase.

Likewise, "species are identified by a clear diagnosis," Spoor says, based on distinct anatomical traits, and using such a shape analysis to determine species "is clearly not adequate," in his view.

Don't "Bring the Whole Bloody House Down"

Wood also points out that the study is entirely focused on skulls. "They are assuming that the only reason that people have come to the conclusion that there was more than one species of early Homo is that it's based entirely on cranial shape, and that's not true," Wood says.

The rest of the skeleton in other early human species carries distinguishing characteristics used to identify distinct species, such as relatively long arms still adapted for climbing in Homo habilis. "It doesn't make any sense to pretend that these pieces of evidence don't exist," Wood says. While he acknowledges that the Dmanisi humans are all likely the same species and can be difficult to categorize as Homo erectus or a separate species, he argues that it's unreasonable to "bring the whole bloody house down" by lumping all early human fossils into a single lineage.

Dmanisi Debate Only a Debut?

So where does that leave the one-time inhabitants of Dmanisi? According to Spoor, their grab bag of skull features places them near an ancient split in human evolution.

The Dmanisi humans have "an interesting combination of a primitive face, primitive teeth, primitive size of the brain," Spoor says, "but if I would take a saw and cut off the face and show the braincase to a colleague, I'm pretty sure that person would say, 'That's Homo erectus.'"

The combination of features seen in the Dmanisi skulls is a record of "evolution in action," Spoor adds. They might place the Dmanisi humans somewhere after the split between the earlier Homo habilis and Homo erectus, sometime prior to 1.8 million years ago.

Debate will undoubtedly continue about who the Dmanisi humans really were and how they fit into our broader family history. Those arguments will hinge on what is still being found. "Dmanisi is a snapshot in time, like a time capsule," Lordkipanidze said at the briefing. He suggests that his discovery team isn't done yet, and more early human fossil finds may lie ahead: "We can say for sure that Dmanisi has enormous potential to yield new discoveries."

Brian Switek

for National Geographic

Published October 17, 2013