Russian Meteor's Two Scary Lessons

Nine months after the incredible air blast of a meteor over Chelyabinsk, Russia, scientists at the Geological Society of America meeting are reporting that the frequency of such air bursts is probably underestimated and these events are more damaging than comparable nuclear blasts.

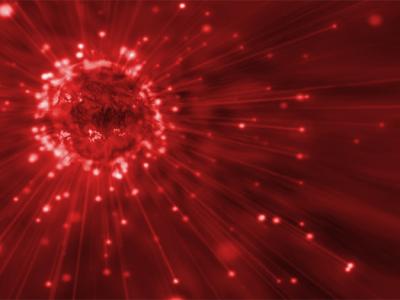

It was on Feb. 15, 2013, that the infamous asteroid exploded in the air about 40 kilometers south-southwest the city of Chelyabinsk. The shock waves shattered windows far and wide, set off alarms, injured many people, but also provided a treasure trove of recorded digital video from security and dashboard cameras.

Combined with seismic, infrasound and satellite data, there was an unprecedented amount of information for researchers like Mark Boslough of Sandia National Laboratories. He and his colleagues used all that data to create a simulation of the event that matched the observations in order to flesh out the information about what happened. They presented their findings at the meeting on Oct. 29.

The videos and other data allowed the trajectory to be worked out and the velocity to calculated very accurately at a brisk 68,400 km per hour (42,500 miles per hour) and at a low angle of 17 degrees. It reached its peak brightness 29 kilometers up (18 miles). From this they calculated that before the meteor hit our atmosphere, it was about 20 meters in diameter and weighed about 1,200 tonnes (1,300 U.S. tons).

From satellites sensors that recorded flash of light — which is estimated to be 20 percent of the total energy released by the meteor — put the radiant energy at about 90 kilotons. So that number times five gives a total energy of 450 kilotons, which agrees with infrasound and other measurements, the researchers report. Because the meteor entered at such a low angle, all that explosive energy was released along a line over 16.5 seconds — which was a good thing.

“The blast was distributed over a large area, and was much weaker than for a steep entry and a more concentrated explosion closer to the surface,” the researchers report.

“Chelyabinsk and Tunguska are ‘once-per-century’ and ‘once-per-millennium’ events, respectively. These outliers imply that the frequency of large airbursts is underestimated. Models also suggest that they are more damaging than nuclear explosions of the same yield (traditionally used to estimate impact risk). The risk from airbursts is therefore greater than previously thought.”

Image: The smoky trace of the Chelyabinsk meteor moments after it entered the atmosphere and exploded on Feb. 15, 2013. Credit: Wikimedia Commons, Nikita Plekhanov.(Oct 30, 2013 09:14 AM ET // by Larry O'Hanlon)