Can Purported Mammoth Blood Revive Extinct Species?

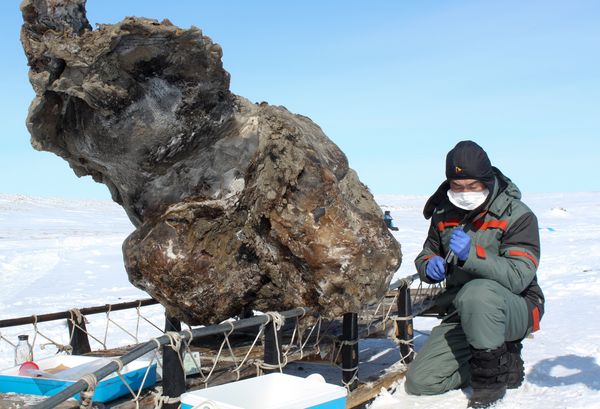

The carcass of a female mammoth found in Russia that researchers say includes 10,000-year-old mammoth blood.

Mammoth blood won't bring us any closer to cloning adorable baby woolly mammoths. That is, if the substance ballyhooed in news reports really is mammoth blood to begin with.

Despite this week's breathless stories heralding the discovery of mammoth blood and the prospect of recreating the shaggy beasts, relatively little is known about the find.

Like other previously discovered mammoths, the roughly 10,000-year-old specimen recently found among Russia's Novosibirsk Islands remained wonderfully intact in the northern deep freeze. The old female mammoth appears to preserve a great extent of soft tissues over the carcass, according to early reports.

But a peculiar liquid found around the carcass is what has been making headlines.

North-Eastern Federal University mammoth expert Semyon Grigoriev, who spearheaded the excavation of the mammoth, has publicly speculated that this fluid is mammoth blood that may contain viable cells. This would seem to bring the possibility of resurrecting a mammoth closer than ever before, but the scientific truth is that we're still a long way from even hoping for such a feat.

Scientists say they found this well-preserved muscle in the mammoth carcass.

Photograph from Semyon Grigoryev, Northeastern Federal University/AFP/Getty Images

No one knows what the dark fluid that seeped from beneath the mammoth really is, much less whether the liquid contains cells from the beast. "Whatever we want to call the red material, it would be fantastic if it contained intact cells," says Ross Macphee, an Ice Age mammal expert at the American Museum of Natural History. "I await secure identification on this point."

Long Odds of Mammoth Clone

Beth Shapiro, an expert on ancient DNA at the University of California, Santa Cruz, says she is "super excited" about the find of such a large, relatively intact mammoth, adding, "I don't think it's impossible that there is some blood in such a well-preserved find."

Despite that chance, though, Shapiro says, "I strongly, strongly suspect that there will be zero intact cells in the find, regardless of whether blood is preserved."

That dampens dreams of seeing mammoths walk again. "Without an intact, functional cell—one that can be de-differentiated into a stem cell in a petri dish—one cannot clone this animal," she says.

And Shapiro laments that the focus on cloning has distracted the public from the great deal of useful biological information the new mammoth might really provide researchers.

"I'm even a little bit sad, but not surprised, about all the cloning hype that has immediately come out," Shapiro says, "as I think it detracts from the real work that paleontologists, molecular biologists, physiologists, et cetera, could do with such an important find. The media are crying wolf."

When mammoths make news, though, the prospect of cloning them always follows. The reality is messier.

"We are still a great distance away from cloning anything like a mammoth," Macphee says. A critical step is piecing together a complete genetic profile of a mammoth, a problem that the new mammoth fluid won't solve, no matter what it turns out to be.

DNA begins to break down at death, so paleogeneticists would likely draw only scraps of genetic material from the mammoth. Then they would try to place those scraps into a DNA patchwork of the best approximation of what we think a mammoth's genome would be like.

The result would not be a resurrected woolly mammoth genome; it would be modern science's best approximation of mammothness.

That's to say nothing of actually creating a baby mammoth. Researchers could try to manipulate the sex cells of modern Asian elephants—the closest living relatives to mammoths—to get a mother Asian elephant to carry a mammoth baby, or genetic engineers could alter the genome of elephants bit by bit until they reverse-engineered a living hypothesis of a woolly mammoth.

But researchers are not even close to those experimental steps.

Real Species Revival Movement

Our long-running fascination with bringing mammoths, or something extremely mammoth-like, back to life fall under the controversial movement of "de-extinction." Seeking to undo the ecological wounds humans have contributed to in the past, various scientific groups are aiming to recreate species such as the woolly mammoth, passenger pigeon, and mouth-brooding frog.

Cloning is the most oft-discussed de-extinction option, but such efforts face substantial hurdles, from reconstituting an organism's genome to birth defects that cause clones to have relatively short lives after birth. A recently cloned Pyrenean ibex - a horned, hoofed mammal that went extinct in 2000 - died only a few minutes after it was born.

Another route is to take the nearest relative of an extinct species and modify that animal into the form of the lost species.

But organisms are not simply organic buckets of genes. An elephant modified to have the genes of a woolly mammoth might not have the exact appearance or behavior of the lost species, given the complicated influences of development and environment on what an organism is.

The third option for species revival isn't viable for woolly mammoths. Called breeding back, the process relies on taking domestic animals and selecting traits that more closely resemble those of their wild ancestors.

This kind of project is being undertaken to recreate huge wild cattle called aurochs, which once roamed Europe. But given the lack of domesticated shaggy elephants, it won't work for mammoths.

All these routes to revival presume that the reinvention of lost species is a worthwhile pursuit. The process could teach us a great deal about the genetics and biology of vanished species, but is trying to find a place for Ice Age mammoths in a warming world actually a good idea?

"Too much of the discussion on de-extinction has been very 'gee-whiz science,' focusing too much on the challenge of cloning individuals and not enough on a species' ecological context," says Jacquelyn Gill, a paleoecology postdoctorate at Brown University.

Many questions about mammoths and their ecology, from how many individuals would be needed to sustain a population to the future prospect of how the animals would react to mammoth ecotourism, remain unanswered.

And while some researchers think of recreating extinct species, we continue to lose unique organisms in our own time.

"It's irresponsible to put limited conservation dollars into bringing an Ice Age species into a warming world where dozens of elephants have been slaughtered just this year for their ivory," says Gill.

Brian Switek

for National Geographic

Published June 1, 2013