Brown Dwarf Exoplanet Identified

Brown Dwarf Exoplanet Identified

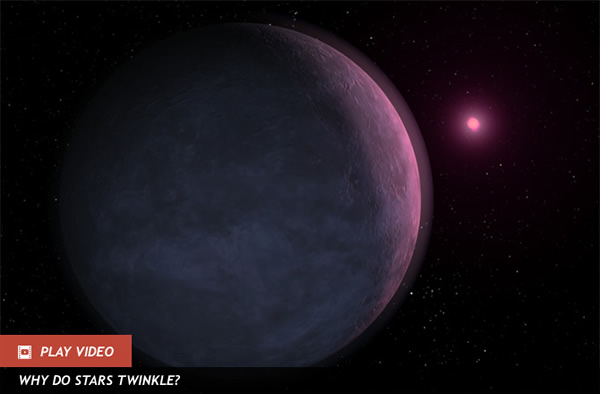

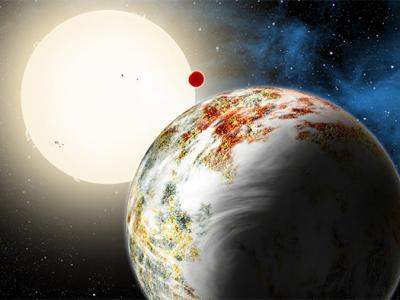

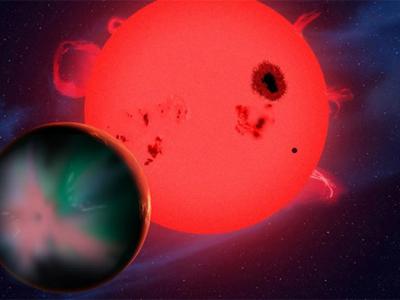

Brown dwarfs are often referred to as “failed stars,” but that moniker may have to be slightly modified to reflect one brown dwarf’s ability of birthing planets — a very star-like trait.

Mysterious brown dwarfs have fascinated astronomers for decades, but only now are we able to observe them in any detail and truly understand their nature. Generally speaking, brown dwarfs are thought to form in a similar way to stars. However, they didn’t accrue enough mass from their stellar nursery to ignite fusion in their cores. Although there is some low-level fusion activity of deuterium and lithium in the cores of brown dwarfs, they certainly cannot fuse hydrogen (the “gold standard” of any self-respecting star) and can only be detected by their infrared emissions.

But just because they aren’t shining doesn’t mean they should be ignored — on the contrary. Brown dwarfs provide a critical insight as to what makes a planet and what makes a star. They are a bridge of sorts, ranging between 13 to 80 Jupiter masses — too massive to be called planets; too small to be called stars; yet possessing characteristics of both. But can they support planetary systems?

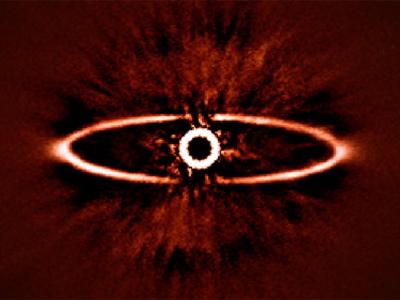

Astronomers have long looked at brown dwarfs for hints of planets. After all, if brown dwarfs are formed in a similar way to stars, shouldn’t they at some stage possess protoplanetary disks and eventually create planets?

Recently, astronomers have spotted young brown dwarfs sporting candidate protoplanetary disks, suggesting some planet-building potential. Also, other brown dwarfs have been discovered with a large planetary mass in tow. But after analysis of the mass and orbital distance, the consensus is that these masses could actually be other, smaller brown dwarfs creating a binary system. One brown dwarf, MOA-2007-BLG-192L, is known to host a small world of approximately 3.3 times the mass of Earth, but other examples have been hard to come by.

But now an international collaboration of astronomers appear to have found another likely brown dwarf exoplanet.

The Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) project — a 1.3 meter telescope operated by the University of Warsaw at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile — was monitoring a microlensing event as a brown dwarf drifted in front of a distant star. Through a quirk of Einstein’s general relativity, the mass of the brown dwarf warps the spacetime around it. As the light travels from the distant star, it gets bent around the brown dwarf. If Earth is positioned just right, the geometry of this cosmic alignment has a magnifying effect, lensing the starlight for a short time. These microlensing events are very powerful for measuring the lensing object’s mass and it can be used as an effective expolanet detection tool. MOA-2007-BLG-192Lb was also discovered through microlensing.

During this particular event, designated OGLE-2012-BLG-0358, OGLE detected the amplified star’s lightcurve. After careful analysis and followup studies by other telescopes, a secondary “bump” in the lightcurve was evident. The researchers reported the detection of a “relatively tightly-separated (0.87 AU) binary composed of a planetary-mass object with 1.9 (+/-0.2) Jupiter masses orbiting a brown dwarf with a mass of 0.022 solar masses.” In other words, an exoplanet nearly twice the mass of Jupiter has been found orbiting its host brown dwarf at a distance a little under the distance Earth orbits the sun. Although other candidates exist, this is one of the smallest planetary candidates to be found orbiting a brown dwarf.

This research has been made available through the arXiv preprint service and submitted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal.

The researchers admit that further theoretical study is needed to help explain how the planet formed, but taking its low mass and compact orbit into consideration, it seems highly likely that it formed from a protoplanetary disk when the brown dwarf was young, in a similar fashion to how regular stars spawn planets.

“Microlensing surveys for exoplanets are well-suited to detect planetary companions to very faint, low-mass stars and old brown dwarf systems which are difficult to discover via other methods,” the researchers write. “The last two decades have witnessed tremendous progress in microlensing experiments, which have enabled a nearly 10-fold increase in the observational cadence, resulting in an almost 100-fold increase in the event detection rate. With this observational progress, the number of BD events with precisely measured physical parameters is rapidly increasing.”

Far from being “failed stars,” it seems that brown dwarfs are proving themselves to be perfectly capable of spawning their own, albeit dimmer, planetary systems. And it looks like we’ve only just glimpsed into the highly secretive lives of objects in our Milky Way that didn’t quite make it to stellar proportions.

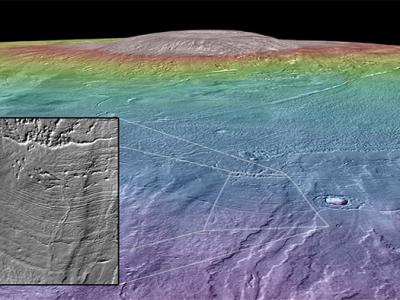

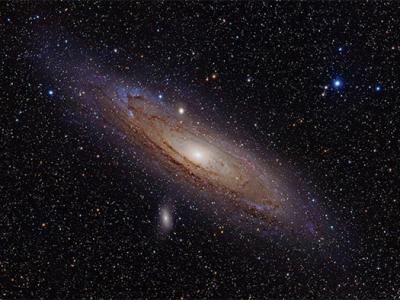

Image credit: NASA(Brown dwarfs are often referred to as “failed stars,” but that moniker may have to be slightly modified to reflect one brown dwarf’s ability of birthing planets — a very star-like trait.

Mysterious brown dwarfs have fascinated astronomers for decades, but only now are we able to observe them in any detail and truly understand their nature. Generally speaking, brown dwarfs are thought to form in a similar way to stars. However, they didn’t accrue enough mass from their stellar nursery to ignite fusion in their cores. Although there is some low-level fusion activity of deuterium and lithium in the cores of brown dwarfs, they certainly cannot fuse hydrogen (the “gold standard” of any self-respecting star) and can only be detected by their infrared emissions.

But just because they aren’t shining doesn’t mean they should be ignored — on the contrary. Brown dwarfs provide a critical insight as to what makes a planet and what makes a star. They are a bridge of sorts, ranging between 13 to 80 Jupiter masses — too massive to be called planets; too small to be called stars; yet possessing characteristics of both. But can they support planetary systems?

Astronomers have long looked at brown dwarfs for hints of planets. After all, if brown dwarfs are formed in a similar way to stars, shouldn’t they at some stage possess protoplanetary disks and eventually create planets?

Recently, astronomers have spotted young brown dwarfs sporting candidate protoplanetary disks, suggesting some planet-building potential. Also, other brown dwarfs have been discovered with a large planetary mass in tow. But after analysis of the mass and orbital distance, the consensus is that these masses could actually be other, smaller brown dwarfs creating a binary system. One brown dwarf, MOA-2007-BLG-192L, is known to host a small world of approximately 3.3 times the mass of Earth, but other examples have been hard to come by.

But now an international collaboration of astronomers appear to have found another likely brown dwarf exoplanet.

The Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) project — a 1.3 meter telescope operated by the University of Warsaw at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile — was monitoring a microlensing event as a brown dwarf drifted in front of a distant star. Through a quirk of Einstein’s general relativity, the mass of the brown dwarf warps the spacetime around it. As the light travels from the distant star, it gets bent around the brown dwarf. If Earth is positioned just right, the geometry of this cosmic alignment has a magnifying effect, lensing the starlight for a short time. These microlensing events are very powerful for measuring the lensing object’s mass and it can be used as an effective expolanet detection tool. MOA-2007-BLG-192Lb was also discovered through microlensing.

During this particular event, designated OGLE-2012-BLG-0358, OGLE detected the amplified star’s lightcurve. After careful analysis and followup studies by other telescopes, a secondary “bump” in the lightcurve was evident. The researchers reported the detection of a “relatively tightly-separated (0.87 AU) binary composed of a planetary-mass object with 1.9 (+/-0.2) Jupiter masses orbiting a brown dwarf with a mass of 0.022 solar masses.” In other words, an exoplanet nearly twice the mass of Jupiter has been found orbiting its host brown dwarf at a distance a little under the distance Earth orbits the sun. Although other candidates exist, this is one of the smallest planetary candidates to be found orbiting a brown dwarf.

This research has been made available through the arXiv preprint service and submitted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal.

The researchers admit that further theoretical study is needed to help explain how the planet formed, but taking its low mass and compact orbit into consideration, it seems highly likely that it formed from a protoplanetary disk when the brown dwarf was young, in a similar fashion to how regular stars spawn planets.

“Microlensing surveys for exoplanets are well-suited to detect planetary companions to very faint, low-mass stars and old brown dwarf systems which are difficult to discover via other methods,” the researchers write. “The last two decades have witnessed tremendous progress in microlensing experiments, which have enabled a nearly 10-fold increase in the observational cadence, resulting in an almost 100-fold increase in the event detection rate. With this observational progress, the number of BD events with precisely measured physical parameters is rapidly increasing.”

Far from being “failed stars,” it seems that brown dwarfs are proving themselves to be perfectly capable of spawning their own, albeit dimmer, planetary systems. And it looks like we’ve only just glimpsed into the highly secretive lives of objects in our Milky Way that didn’t quite make it to stellar proportions.

Image credit: NASA(Brown dwarfs are often referred to as “failed stars,” but that moniker may have to be slightly modified to reflect one brown dwarf’s ability of birthing planets — a very star-like trait.

Mysterious brown dwarfs have fascinated astronomers for decades, but only now are we able to observe them in any detail and truly understand their nature. Generally speaking, brown dwarfs are thought to form in a similar way to stars. However, they didn’t accrue enough mass from their stellar nursery to ignite fusion in their cores. Although there is some low-level fusion activity of deuterium and lithium in the cores of brown dwarfs, they certainly cannot fuse hydrogen (the “gold standard” of any self-respecting star) and can only be detected by their infrared emissions.

But just because they aren’t shining doesn’t mean they should be ignored — on the contrary. Brown dwarfs provide a critical insight as to what makes a planet and what makes a star. They are a bridge of sorts, ranging between 13 to 80 Jupiter masses — too massive to be called planets; too small to be called stars; yet possessing characteristics of both. But can they support planetary systems?

Astronomers have long looked at brown dwarfs for hints of planets. After all, if brown dwarfs are formed in a similar way to stars, shouldn’t they at some stage possess protoplanetary disks and eventually create planets?

Recently, astronomers have spotted young brown dwarfs sporting candidate protoplanetary disks, suggesting some planet-building potential. Also, other brown dwarfs have been discovered with a large planetary mass in tow. But after analysis of the mass and orbital distance, the consensus is that these masses could actually be other, smaller brown dwarfs creating a binary system. One brown dwarf, MOA-2007-BLG-192L, is known to host a small world of approximately 3.3 times the mass of Earth, but other examples have been hard to come by.

But now an international collaboration of astronomers appear to have found another likely brown dwarf exoplanet.

The Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment (OGLE) project — a 1.3 meter telescope operated by the University of Warsaw at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile — was monitoring a microlensing event as a brown dwarf drifted in front of a distant star. Through a quirk of Einstein’s general relativity, the mass of the brown dwarf warps the spacetime around it. As the light travels from the distant star, it gets bent around the brown dwarf. If Earth is positioned just right, the geometry of this cosmic alignment has a magnifying effect, lensing the starlight for a short time. These microlensing events are very powerful for measuring the lensing object’s mass and it can be used as an effective expolanet detection tool. MOA-2007-BLG-192Lb was also discovered through microlensing.

During this particular event, designated OGLE-2012-BLG-0358, OGLE detected the amplified star’s lightcurve. After careful analysis and followup studies by other telescopes, a secondary “bump” in the lightcurve was evident. The researchers reported the detection of a “relatively tightly-separated (0.87 AU) binary composed of a planetary-mass object with 1.9 (+/-0.2) Jupiter masses orbiting a brown dwarf with a mass of 0.022 solar masses.” In other words, an exoplanet nearly twice the mass of Jupiter has been found orbiting its host brown dwarf at a distance a little under the distance Earth orbits the sun. Although other candidates exist, this is one of the smallest planetary candidates to be found orbiting a brown dwarf.

This research has been made available through the arXiv preprint service and submitted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal.

The researchers admit that further theoretical study is needed to help explain how the planet formed, but taking its low mass and compact orbit into consideration, it seems highly likely that it formed from a protoplanetary disk when the brown dwarf was young, in a similar fashion to how regular stars spawn planets.

“Microlensing surveys for exoplanets are well-suited to detect planetary companions to very faint, low-mass stars and old brown dwarf systems which are difficult to discover via other methods,” the researchers write. “The last two decades have witnessed tremendous progress in microlensing experiments, which have enabled a nearly 10-fold increase in the observational cadence, resulting in an almost 100-fold increase in the event detection rate. With this observational progress, the number of BD events with precisely measured physical parameters is rapidly increasing.”

Far from being “failed stars,” it seems that brown dwarfs are proving themselves to be perfectly capable of spawning their own, albeit dimmer, planetary systems. And it looks like we’ve only just glimpsed into the highly secretive lives of objects in our Milky Way that didn’t quite make it to stellar proportions.

Image credit: NASA(Jul 26, 2013 09:01 PM ET // by Ian O'Neill)