Did Ancient Sea Monster Turn Prey Into Art?

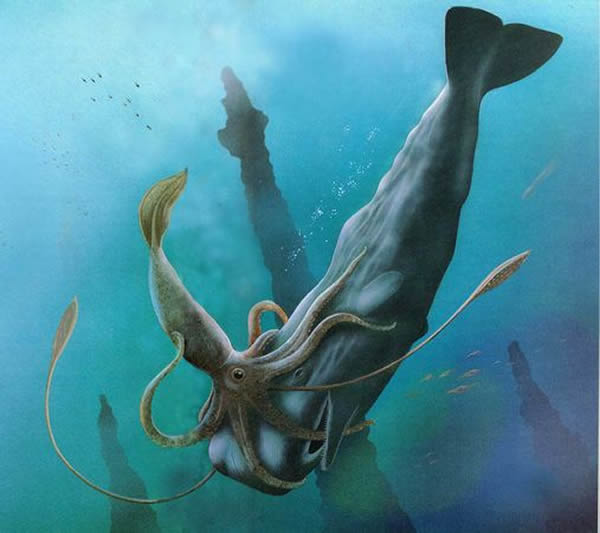

Debate over the possible existence of an ancient kraken (shown fighting a sperm whale in the illustration above) has resurfaced at a scientific meeting.

An intelligent ancient squid that rearranged the backbones of its prey into art? Fossil experts call it a fable, but one expert says to believe it.

The "kraken" has resurfaced at a scientific meeting, and is certain to stir controversy once more.

"The Kraken's Back" is the title of the talk presented Wednesday at the annual Geological Society of America (GSA) meeting in Denver by paleontologist Mark McMenamin of Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts.

"I can say we have found the tip of the beak of the Triassic kraken," says McMenamin. His proof? A fossilized squid's "pen"—a chitinous paddle found inside squid mantles—that dates to about 218 million years ago.

Although the newfound fossilized pen, which McMenamin presented at his talk, is only a few inches long and incomplete, the paleontologist estimates that the ancient squid it belonged to was 50 to 100 feet (16 to 30 meters) long. At the meeting he called it "school bus-sized." Modern giant squids may grow to about 40 feet (12 meters) long.

A Triassic kraken beak tip found by McMenamin.

Most remarkably, at the meeting McMenamin repeated a suggestion he had made previously: that these ancient giant squids made art, arranging the backbones of their prey into mosaics in their lairs, in a bid at self-portraiture.

As evidence, he cited a Nevada State Museum exhibition from three decades ago that had included a display of a mosaic similar to one he had noted in 2011, when he first made this argument, and similar to one found at the fossil site where the pen was discovered.

But others aren't convinced.

Suggesting the kraken made art "is kind of a strange argument," says paleontologist David Fastovsky of the University of Rhode Island in Kingston.

"It is one thing to claim the discovery of a large, ancient squid. But going beyond that takes us far away from what most paleontologists would see as reasonable."

Monster Controversy

In 2011, McMenamin had reported that his team had discovered the lair of an ancient giant squid or octopus at a Nevada fossil site. His evidence, which he cited at the annual GSA meeting that year, is a fossilized arrangement of nine ichthyosaur backbones embedded in a mosaic pattern.

Ichthyosaurs were marine reptiles that resembled dolphins; McMenamin theorizes that they were food for the kraken. He claims the creatures brought their prey down to a trash-filled lair and arranged their backbones into patterns resembling that of suckers lining their arms.

The suggestion had triggered a flood of critical comments from paleontologists, including Donald Prothero of Occidental College in Los Angeles, who called it absurd.

Prothero still feels that way two years later, saying by email that McMenamin "has mined this unreviewed [meeting] abstract for LOTS of free publicity, and gullible reporters think that his work has passed muster because it's presented at these meetings.

"But NOT ONE scientist at these meetings takes him seriously."

McMenamin defended his findings in an interview prior to the presentation, saying the newfound pen fossil provides evidence that critics of his 2011 presentation then called lacking.

McMenamin does regularly present other research at the meeting—for example, he reported the finding of an ancient oversize crustacean from the same era as the kraken, recently published in the Journal of Crustacean Biology.

Kraken Criticism

Given the attention that the kraken received in 2011, the Paleontological Society, a sponsor of the session at the GSA meeting where the pen fossil was presented, asked Fastovsky to respond to its latest emergence.

Fastovsky is more measured in his criticism of the kraken idea, saying that "finding an ancient, giant squid would be a wonderful discovery.

"If we have a fossil pen, then that is good—we can compare it to other fossils and discuss what sort of squid it once belonged to," Fastovsky says. "I think most paleontologists would think that would be great."

However, he points out that squids, unlike octopuses, don't create trash-filled lairs for their food. "So, right there, that is a problem with the 'kraken arranging bones' idea, if what he has found is a squid."

Outside scientists need to analyze the fossil to determine whether it belonged to a squid, he adds.

Furthermore, while McMenamin maintains that the backbones found in mosaic patterns seem to have been ordered in intelligent fashion, Fastovsky disagrees.

He says that the mosaic resembles the sort of assembly that currents would have created over time as rotting ichthyosaur backbones spilled across the ocean floor.

Occam's Razor

The real problem with the kraken notion is that it violates the scientific principle of favoring the simplest possible explanations for natural phenomenon, Fastovsky adds.

"Parsimony is the basic principle behind everything we do in science.

"The extra suggestion of intelligence in the [backbone] patterns is just unnecessary," he says.

"You really have to ask, is this science or not?"

Dan Vergano

National Geographic

Published October 30, 2013