Why the Hunt for Extraterrestrial Life is Important

On Wednesday, something remarkable happened at Capitol Hill. In a special hearing, lawmakers of the House Science Committee discussed the search for extraterrestrial life with three experts for 2 hours. The question and answer session focused around efforts to find everything from alien microbes under rocks on Mars to full-blown SETI efforts to seek out transmitting extraterrestrial intelligence.

Naturally, some of the questioning was naive and sometimes needlessly lighthearted. In response to the Republican-led House panel, a Democratic opposition group even seized the opportunity to mock the occasion. The hearing was significant; maybe not to the immediate day-to-day running of a nation or the lawmakers who saw it as an entertaining sideshow, but the three scientists invited to talk were dead serious about the opportunities and implications such a high-profile hearing can bring.

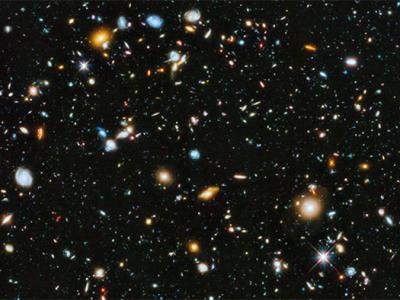

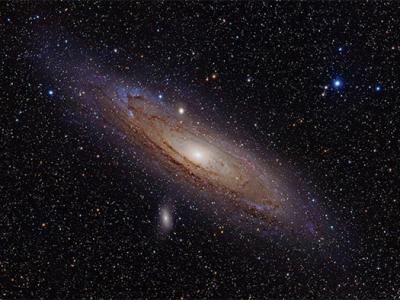

“In our Milky Way galaxy there are 100 billion stars and we now believe, in our universe, we have 100 billion galaxies,” said Sara Seager, Professor of Physics and of Planetary Science at M.I.T., at the hearing titled Astrobiology: The Search for Biosignatures in Our Solar System and Beyond. “So if you just do the math, the chances that there’s a planet like Earth out there with life on it is very high.”

Seager was joined by Mary Voytek, Senior Scientist for Astrobiology in the Science Mission Directorate at NASA headquarters, and Steven J. Dick, Baruch S. Blumberg Chair of Astrobiology, Library of Congress. All discussed their motivations for studying astrobiology and how it inspires youngsters to pursue a career in science. They even outlined the key risks to the future of our species, identifying overpopulation, asteroid impacts and energy shortages as the key factors.

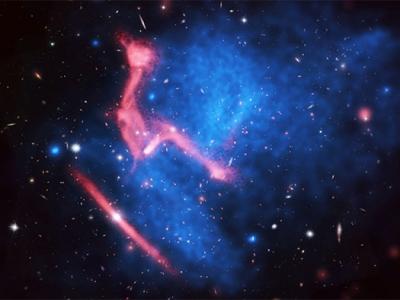

NASA is currently looking for biosignatures that could be indicative of the spawning of basic forms of life beyond Earth. The most high-profile current mission, the Curiosity rover, is not directly looking for life however, it’s seeking out the habitable potential of Mars. Directly hunting down alien biology isn’t the purpose of the Mars Program, so the U.S. space agency has directed its astrobiology mission toward looking for evidence of past and present habitability of the Red Planet.

But other projects are under way, not to seek out how habitable Martian rocks are (or were), but to look out for tell tail narrow-band radio signals, for example, that could only be transmitted by an intelligent civilization. The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI), however, is not a government-funded effort. This wasn’t always the case; SETI used to be a NASA-headed project, a point underscored by Dick’s testimony.

“Almost exactly twenty years ago, in the same session that saw the demise of the Superconducting Super Collider, the 103rd Congress terminated the NASA Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) program,” he said. Now, the alien hunting component of SETI Institute is a privately-funded project, but its facilities are used extensively by other government funded projects . Dick went on to request that NASA funding be reallocated to the endeavor — the search for alien life, after all, inspires the public and should be considered — but in this time of austerity and shrinking government budgets, that’s probably not going to happen.

Of course, the slightest mention of “alien life” inspires visions marauding aliens hellbent on probing humans, a popular Hollywood storyline that Seager was keen to dampen.

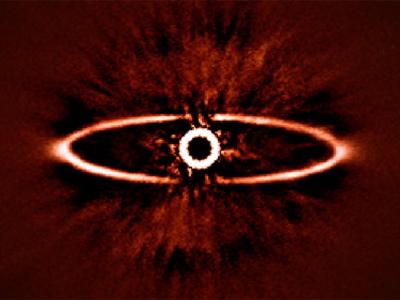

“We’re not looking for UFOs or little green people, what we’re looking for are planets like Earth that orbit stars other than the sun,” Seager told the Washington Post shortly after the meeting.

As if to underline the popular viewpoint whenever “extraterrestrial” is mentioned, during the hearing Rep. Ralph Hall (R-Texas) asked the experts: “Do you think there’s life out there? (laughter) And are they studying us and what do they think of New York City?” The question was followed by more laughter.

At best, the laughter is due to ignorance of the efforts that are under way to discover our place in the universe. At worst, it’s a middle finger at science from the highest echelons of the U.S. government. Or perhaps Rep. Hall is just a funny guy. Regardless, the attitudes by government officials toward one of the noblest scientific endeavors humanity has ever undertaken is saddening — though not unexpected.

Even more frustrating was the response of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee who issued a news release mocking House meeting.

“No wonder the American people think this Republican Congress is from another planet — they’re more interested in life in space than Americans’ lives,” said the DCCC’s Emily Bittner. “Saying this Republican Congress has misplaced priorities is an understatement of galactic proportions.” (Emphasis added.)

And there it is: Discussing the search for extraterrestrial life is a waste of time considering all the other far more pressing concerns a government should be focusing on. In the rush to score political points, the DCCC neglected to consider the scientific, philosophical and historic implications of our desire to understand the nature of life itself and whether life is possible somewhere else in the Universe. That’s not to say that the Republican-dominated committee has a better grasp of this, but this is just one example of the partisan one-upmanship that plagues governments, stymieing some of the most fundamental of scientific pursuits. There will always be more immediate problems for governments to focus on, but that doesn’t mean governments can’t spend a tiny amount of time and resources on inspirational pursuits.

Space science enriches civilization in ways in which may not fully comprehend. The technological spinoffs, for example, are a tangible reminder that advancing our scientific know-how can invigorate developments such as satellite technology, materials science, medical breakthroughs and the miniaturization of computing (to name just a few). On a wider scale, these advances invigorate education, skills, employment and the economy. These things are a direct consequence of our nature to explore and push the envelope.

Technology is one thing, but I would argue that even more than that, developing an understanding as to our place in the Universe is key to the survival of our species. And at the root of this knowledge is the appreciation that we may not be the only life in the Universe. Currently, there is absolutely zero direct evidence of life anywhere else in our galactic neighborhood, intelligent or otherwise. This is a fundamental problem, particularly if you are applying for taxpayer funds for the search for hypothetical extraterrestrial biology, but it has only been a few decades since we even thought to look. In a galaxy that is nearly as ancient as the 13.75 billion year old Universe, we are barely a blip on the biological radar, we stand little chance of finding alien life within the next political cycle.

While we fester, argue, live and die on this small life-giving globe, far grander mechanisms are at play. We occupy a tiny part of interstellar space, orbiting an “average” star that is embedded in an “average” galaxy in a not-so special part of the Universe. Despite the fact that the Copernican Principal seems to govern our existence, we are here, having evolved from a primordial soup of organic chemistry into what appears to be (at least from our perspective) an intelligent race that questions how we are even here and whether there are other civilizations out there asking the same things.

In this modern era, we are becoming less dependent on myth and religion to provide us with answers. Science has given us a skill set that can tackle some of the most complex questions we can think to ask. We build powerful particle colliders to peel back the very nature of matter; we are unraveling life’s genetic code in the hope of developing novel therapies to prolong and enrich life; we are developing a mastery of computing where machines have changed the way we communicate and live. But above all, we explore.

A component of our urge to explore is the search for life beyond Earth and if we find the answer, it will transform the way we view the Universe and it will transform how we view life itself.

So as I watched the House Science Committee ask disappointing questions to a trio of accomplished astrobiology experts and the political bullshit it inspired, I realized that as a whole, we are a myopic species that is more concerned with petty point scoring, closed off to the awesome opportunities that are out there for us to explore.

But there is hope. Humanity is at a crossroads in the urge to explore and the technology to help us do so. I just hope we take the opportunity and politics follows the scientists’ and, by extension, the public’s lead.

“One of the most appealing characteristics of astrobiology is that the discipline forces us to ask questions that put in perspective our place in the universe: What are life, consciousness, and intelligence in a universal context, and what are the metaphysical assumptions that underlie our understanding of these concepts? Is there a general theory of living systems, a universal biology as there is a universal physics? What are culture and civilization? What is our place in the 13.8 billion year unfolding of cosmic evolution? Some of these questions bearing on consciousness and intelligence are beyond the scope of the current NASA astrobiology program, but they are nevertheless an important part of the search for life in the universe.” — Steven J. Dick

Image: Dishes from the SETI Allen Telescope Array (ATA). Credit: SETI Institute(Dec 5, 2013 06:58 PM ET // by Ian O'Neill)