New Theory for Why Antarctic Sea Ice Is Growing

It's a global warming paradox.

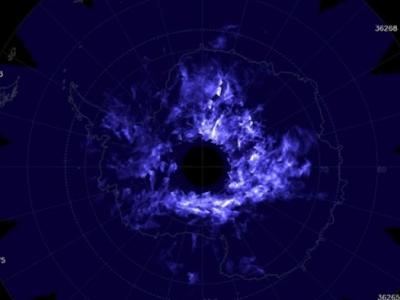

As air and sea temperatures rise, Arctic sea ice is rapidly and uniformly dwindling. In 2012, Arctic sea ice declined so much that the loss "utterly" obliterated the previous record, set in 2007, according to the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center.

As of 2012, the area of Arctic sea ice around the North Pole had shrunk to 1.58 million square miles (4.1 million square kilometers)—the smallest measurement since 1979, when satellite observations began.

But in Antarctica, where sea ice is more scattered and driven by wind and waves, there's another story—ice is increasing in places.

In September of last year, satellite data indicated that Antarctica was surrounded by the greatest area of sea ice ever recorded in the region: 7.51 million square miles (19.44 million square kilometers), according to the center.

Previous studies pointed to snow: Global warming has warmed Antarctic air, and warmer air holds more moisture, which in turn creates more precipitation. That means more snow is falling on Antarctica, and more of the white stuff makes the top layers of the ocean less salty and thus less dense. These layers became more stable, preventing warm currents in the deep ocean from rising and melting sea ice.

Now, a new study has pinpointed another culprit: melting ice shelves. As ice shelves that ring the southernmost continent disintegrate in warming temperatures, the fresh water that flows from them accumulates in a cool

and fresh surface layer on top of the ocean. This cool layer then shields the surface ocean from the warmer, deeper waters that are melting the ice shelves.

The study "shows that global warming can cause regional cooling, and that's quite counterintuitive," said study leader Richard Bintanja, of the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute.

"Most people think if you warm the whole system, it will warm everywhere," he said.

Also counterintuitively, a colder Antarctica may contribute to a rise in sea levels. Colder temperatures mean less snow on the ice sheets, which makes more water stay in the ocean, he pointed out.

Overall, loss of polar ice has contributed about 11.1 millimeters (0.03 feet) to global sea levels since 1992, research shows. Sea levels are rising at a rate of 3.2 millimeters a year.

A leopard seal rests on sea ice between penguin hunts in Antarctica.

Ice Shelves to Blame?

In researching the Antarctic conundrum, Bintanja and colleagues noted routine observations showing that the deepest parts of the ocean off Antarctica are warming.

The team also found research showing that some ice shelves in Antarctica extend up to 0.62 mile (one kilometer) deep into the ocean. The deep warm water can easily come into contact with a shelf and melt it from below.

These observations led the scientists to suggest that the resulting meltwater rises to the surface-fresh water is lighter than saltwater-and forms a cold shallow layer that prevents the warm water from below to mix upward, thus cooling the surface layer and allowing more sea ice to form.

A climate model behaved in the same way, reinforcing the theory, said Bintanja, whose study appears March 31 in the journal Nature Geoscience.

What's more, the team said their new theory can account for most of the sea ice expansion. For instance, a statistical model suggested that other factors, such as precipitation and winds, are responsible for only about 25 percent of sea ice growth.

"A Complicated Place"

Walt Meier, of the U.S. National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado, said the new study is "pretty interesting—it's something that I haven't seen before."

But he's more cautious about the study's claim that melting ice shelves account for the overall trend, he said.

Sea ice can be found far from the edges of the continent, especially in winter when the ice is at its maximum cover, he noted.

"When ice is way far from the coast, the shelf water seems unlikely to have a major effect" on making more sea ice, he said—rather, melting ice shelves may give sea ice formation "a head start."

Noted study leader Bintanja: "We tested this with our climate model, and the effect of meltwater does extend all the way to the sea ice front."

Overall, Meier said, all of the dynamics in Antarctica—from wind to temperature to weather—makes it difficult to ferret out the facts.

"It's a complicated place."

Christine Dell'Amore

National Geographic News

Published March 29, 2013