'Noisy' Icebergs Could Mask Whale Calls

A rare photo showing a humpback whale next to sea ice or part of an iceberg in the Weddell Sea. The picture was snapped by researchers during a January 2013 expedition.

The sound of icebergs breaking apart in the ocean could make the seas a noisier place. In turn, whales and other cetaceans could have a harder time hearing other animals' calls in the din when icebergs are calving, new research suggests.

Scientists generally agree that the North Atlantic has become noisier in the last 30 years, with commercial shipping traffic and storms the main culprits.

"Recent reports have said that especially near port of calls in industrial countries, noise levels rose about 10 decibels in the last 30 to 40 years," said study co-author Haru Matsumoto, an acoustic engineer at Oregon State University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "That's almost three times noisier."

Many marine biologists worry that the louder oceans could make it hard for whales, porpoises and dolphins to hear other calls, locate prey or navigate.

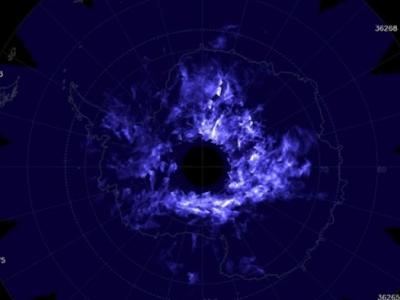

But the waters around Antarctica see much less vessel traffic, so less was known about the noise in the southern waters. Matsumoto and his colleagues were tracking the sounds from hydrophones, or underwater microphones, located in the Pacific a few hundred miles from Panama, when they noticed an uptick in noise in 2008. To pinpoint the source, they also analyzed data from Juan Fernandez Island, off the coast of Chile in the Southern Pacific Ocean, ruling out seismic activity and other sources of ocean noise in the region.

Noisy icebergs

It turned out that a massive iceberg called C19 and about the size of Rhode Island, had calved into the ocean and disintegrated that year, Matsumoto said. What's more, the noise could propagate for great distances without much dissipation: Hydrophones in ocean waters more than 5,000 miles (8,000 kilometers) from the calving recorded the change.

The team also looked at several years of data and found consistent seasonal patterns in the Antarctic region. During the winters, when sea ice extent was at its maximum, the noise levels dropped.

"When it goes below freezing, the ocean becomes quiet," Matsumoto, who presented the findings here Monday (Dec. 2) at the 166th meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, told LiveScience.

But once air temperatures rose above freezing, the din increased. That suggests the movement of icebergs into the open ocean was the source of the increase.

"Icebergs are the main noise sources and annual retreat and advance of sea ice extent modulates the sound levels," Matsumoto said.

Warming world, noisier oceans?

The findings hint that as temperatures increase with global warming, some areas, such as Western Antarctica, could see increased iceberg disintegration, which could in turn make for noisier oceans.

The sound of icebergs shattering can overlap with the sound frequencies of some whale and cetacean calls, which are typically lower than is audible by the human ear, Matsumoto said.

But iceberg noise could not only hinder whales' communication, but also that of fish, said Marie Roch, a computer scientist at San Diego State University, who was not involved in the study.

For instance, some evidence suggests that larval fish use sound to navigate to coral reefs to feed. "If it becomes louder, then it's harder for them to find coral reefs," Roch told LiveScience. (Icebergs in this particular region would probably not affect these species of fish, but those in other regions could potentially affect this process, she said.)(Dec 5, 2013 06:30 AM ET // by Tia Ghose, LiveScience)