Neptune and Uranus Possess Weird Jet Streams

Neptune and Uranus Possess Weird Jet Streams

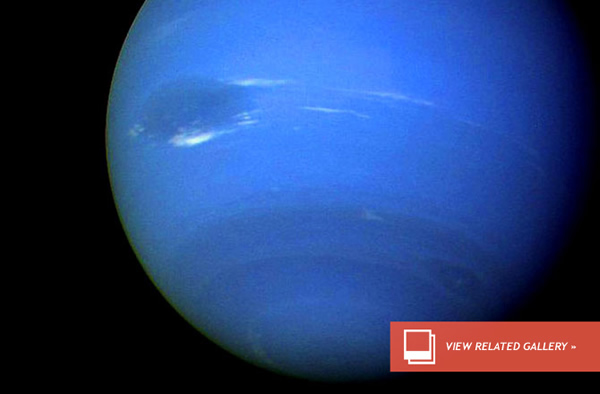

The two planets in our solar system that we probably know the least about are the ice giants, Uranus and Neptune. Distant worlds that we’ve visited only once, courtesy of Voyager 2, what lies beneath their clouds is still very much a mystery. However, they both share one thing in common with Earth — the atmospheres of the two ice giants contain jet streams.

The jet streams on Earth are high in the atmosphere. Powerful streams of wind flowing from East to West, at speeds of over 100 miles per hour (160 km/h). This may sound fast, but Neptune and Uranus aren’t so gentle. Neptune is particularly turbulent, boasting the strongest winds in the entire solar system, reaching speeds of over 1,300 mph (2,100 km/h). But latest results show that those winds are only found in a relatively thin layer of these planets’ atmospheres.

In a recent paper, lead author Yohai Kaspi and a group of researchers based in Israel and the US show that the viciously powerful winds in these worlds are confined to a relatively small region of their atmospheres, no more than 680 miles (1,100 km) deep.

Neptune and Uranus are twins in some respects. They’re very close to one other in size, mass, and composition. They’re also distinctly different to the two larger giant planets, Jupiter and Saturn, in that they contain more molecules like methane, ammonia, and water. While the larger gas giants are mostly hydrogen and helium, these light gasses make up only 20 percent of their colder sister worlds.

Understanding the atmospheres of giant planets can tell us a great deal about how those planets work, but we still know very little about them. Only a handful of spacecraft have ever visited our solar system’s largest worlds, and only one (the Galileo probe in 1995) has ever given us a glimpse of a giant planet, Jupiter, from inside its atmosphere. For a long time, a big question has been whether the winds reach deep into a planet’s atmosphere, or if they’re only found near the surface.

For this study, Kaspi and his colleagues used an ingenious trick. They analysed the gravitational fields of the two ice giant planets to look for how they were affected by winds. The gravitational field of any planet is affected by how dense it is.

In the case of a giant planet, the motion of the swirling winds is matched by a change in the planet’s gravity. For the ice giants, results showed that just 0.15 percent of Uranus and 0.2 percent of Neptune were active, confining the weather on both worlds to a very thin layer.

The question still remains, however, of what powers the winds on these planets. Neptune in particular, has been a puzzle for a long time. It receives very little energy from the sun and has exceptionally cold surface layers, meaning that the powerful winds we see in its atmosphere may be driven by heat from inside the planet.

We may be a long way from knowing exactly how giant planets work, but results like these put us a step closer to fully understanding what goes on inside worlds like these — both within our solar system, and elsewhere.(May 24, 2013 02:19 PM ET // by Markus Hammonds)