Could Earth Germs Colonize Mars?

Could Earth Germs Colonize Mars?

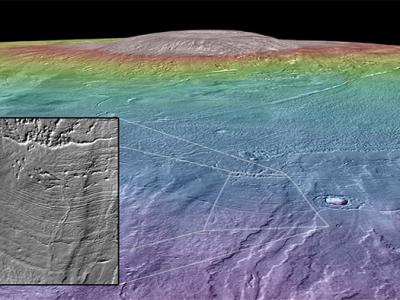

Since its daredevil landing on Mars last summer, NASA’s Curiosity rover has been avidly exploring its new home in Gale Crater. But there’s been one worry that several people have voiced since Curiosity launched — what if the rover contaminates the surface of Mars with Earth life?

Mars and Earth are very different places. Earth’s butterscotchy little brother is a dry and gelid little world. Among its other hazards are surface pressures approaching 1000 times lower than at Earth’s sea level, temperatures which can be low enough to freeze carbon dioxide, and practically no oxygen. Full of curiosity of their own, Wayne Nicholson and Andrew Schuerger, a pair of microbiologists based at the University of Florida, decided to see if certain Earth microbes could take some punishment.

They didn’t choose just any old bacteria though. The microbes in question were taken from samples of Russian permafrost, collected over 12 meters (40 feet) below ground. These bacteria were first nurtured for 28 days in nutrient-rich dishes kept at normal Earth conditions. Then around 10,000 colonies of the bacteria were subjected to 30 days of conditions intended to mimic Mars, at temperatures of 0°C (32°F) and a pressure of just 7 millibars — the same pressure on the surface of Mars.

Six of the bacterial colonies tested, containing a strain known as carnobacterium, managed to grow under these harsh conditions. In fact, surprisingly, the carnobacterium colonies grew better at low pressures and without oxygen than they did under more normal conditions. The reasons why aren’t entirely clear. Schuerger commented, “It appears that at low pressures, an unknown mechanism might kick in that helps them increase the range in which they can grow.”

Six out of 10,000 bacterial colonies may not be an extremely high success rate but, interestingly, Nicholson and Schuerger’s experiments are the first time Earth microbes have ever been successfully grown at such a low pressure. The previous record lowest pressure for bacterial growth was four times higher.

Usually, the tools on craft sent to other planets are sterilized to try and prevent any kind of contamination, but a miscommunication at NASA meant that six months prior to its launch, the drill bits of the Curiosity rover may have been exposed to Earth microbes.

This has even led to the possibility that if Curiosity finds water on Mars, it might be instructed to actively avoid it! The Gale crater was chosen as a site for geological investigation, not to search for water, so this hopefully shouldn’t be a problem — but the problem is still likely on the backs of the minds of those responsible for driving the rover.

The idea of hitchhiking Earth microbes having already found their way to the surface of Mars is not a new one by any means. Nor, for that matter, is the idea of subjecting Earth microbes to the conditions found on our sibling world to see how they fare. Even without the concern over Curiosity’s drilling equipment, there was also concern over its wheels carrying bacteria.

Mind you, it’s still a possibility that life may be able to migrate between the two planets naturally, blasted from one planetary surface to the other by meteorites. There’s currently no way of knowing for certain whether or not this has happened in the past — but it’s entirely possible.

Schuerger and Nicholson, together with other colleagues, also performed a companion study to their experiments. They tested 26 species of bacteria commonly found living on spacecraft, subjecting them to the same harsh conditions. They found one species, Serratia liquefaciens, which managed to both survive and grow.

Where carnobacterium is specialized to live in freezing conditions, serratia liquefaciens is a generalist survival expert. The Ray Mears of the microbial world, s. liquefaciens can survive everywhere from human skin to soil to marine environments. Evidently, even Mars may not be too challenging for it. This study is especially interesting because it shows that while a lot of research has been done into extremophiles — life forms which live in the most extreme environments Earth has to offer — non-specialist life forms should not be ignored.

The biggest difference between the conditions in this experiment and the real surface of Mars is moisture. These bacteria were grown in moisture rich media, while Mars itself is exceptionally arid. Dessication would likely kill off Earth microbes which arrived on Mars quite rapidly. Whether they could survive in any damper conditions which may exist somewhere on the surface of our neighboring planet, however, isn’t certain right now. The Mars Phoenix lander did discover water in the Martian permafrost, after all.

Schuerger noted all the same, that the results which he and Nicholson obtained would “open up much more complex experiments that scientists would not have been able to tackle before because we did not know if anything could grow at 7 millibars.”

“There are 17 ‘biocidal’ factors on the surface of Mars that might kill microbes there, and now we can test more of these factors simultaneously in experiments, such as severely dry conditions and high salt concentrations, to see if these affect microbial growth.” The question of whether Earth microbes really could find a home on Mars is still an open one, though perhaps we might have an answer soon.

Mar 6, 2013 11:29 AM ET by Markus Hammonds