Pygmies' Small Size Linked to Short Life Spans

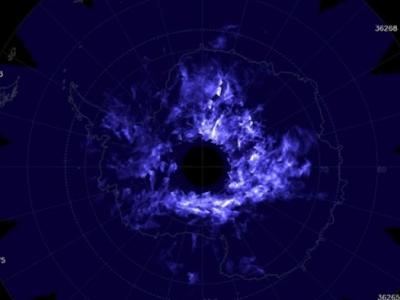

An Aeta shaman plays a bamboo harp in a ritual to exorcise the spirit of death.

The Aeta and other pygmies are smaller in stature because they tend to live very short lives, a new study says. The authors argue that evolutionary pressure—not poor diet—means that the energy needed to grow has been redirected toward early reproduction.

Photograph courtesy Rodolph Schlaepfer

Nicholas Wadhams

for National Geographic News

December 10, 2007

Human pygmies around the world are smaller than average because they tend to live very short lives, in some communities as little as 16 years, a new study says.

Such brief life spans have put evolutionary pressure on pygmy women to stop growing and start having babies sooner, the research suggests. The energy that would typically be used for growth is instead expended on reproduction at a younger age.

"The idea is that [pygmies] have to stop growing earlier, because when you start reproducing—at least for women—all the energy you would put in growth is put into reproduction," said Andrea Migliano, the lead author of the study and a postdoctoral fellow at Clare College, Cambridge, in the United Kingdom.

"You have to choose—either you grow or you reproduce," she said.

Evolution, Not Nutrition?

Migliano's paper, published in this week's online edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, challenges the commonly held belief that pygmies' small stature is the result of environmental factors such as poor nutrition.

Migliano said she was suspicious of that idea, because some of the world's tallest people—such as Kenya's Maasai and Samburu—also typically suffer from poor nutrition.

Instead, Migliano suggests, stature is the result of an evolutionary process woven into pygmies' genetic structure and would not change quickly if pygmies were subjected to less stressful environments.

Pygmies are defined as populations with an average male height of less than five feet (one and a half meters). People of that description are found all over the world, from Brazil to Papua New Guinea.

Migliano and her colleagues studied two populations of pygmies in the Philippines, the Aeta and the Batak.

Mortality is high in these communities because the populations are ravaged by easily preventable diseases, such as measles and chicken pox. Their diets are also poor, making them more susceptible to illness, Migliano said.

Migliano's data are partly supported by similar work done by other scientists.

James Eder, an anthropologist at Arizona State University in Tempe, collected data in the 1980s showing that Batak women reached menopause as early as 28 or 29 years old.

"The most distinctive thing I could say about [the Batak], other than the superficial things, is this business about a pop where women are shutting down their reproductive cycling," Eder said.

"I found cases of women 28 years old who said they no longer experienced menstruation. Very few births were occurring to women more than 30 years of age," he said.

Eder allowed Migliano to use some of his data but did not participate in her research.

"Life History" Theory

Theories similar to Migliano's hypothesis have been used to explain the difference in size between other kinds of mammals, such as elephants and mice.

"The broad variation in size across mammals goes with extreme variation in the pace of life histories—little-bitty ones live fast and die young, and big ones live slowly and die old," said Kristen Hawkes, an anthropologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City who edited Migliano's paper.

"Links between body size and life history have been applied to species changes over time within our lineage, but [Migliano] is the one who's taken this theory to look at within-species variation among living people."

Migliano's theory will no doubt be controversial, particularly among creationists and proponents of intelligent design, because it proposes that pygmies are proof of how our species, Homo sapiens, continues to evolve.

(Read related story: "Evolution Less Accepted in U.S. Than Other Western Countries, Study Finds" [August 10, 2006].)

"There is this idea that evolution should not apply for humans," noted Migliano, who said she had already gotten some criticism for putting her theory forward.

She added that she is also pressing the government of the Philippines to improve pygmies' living conditions.

"I am sure we are still adapting to our environment," she said. "But saying we are adapting to our environment doesn't say that the pygmies are fine. They are adapting to the worst situation in the world."