How Curiosity Took a Self-Portrait

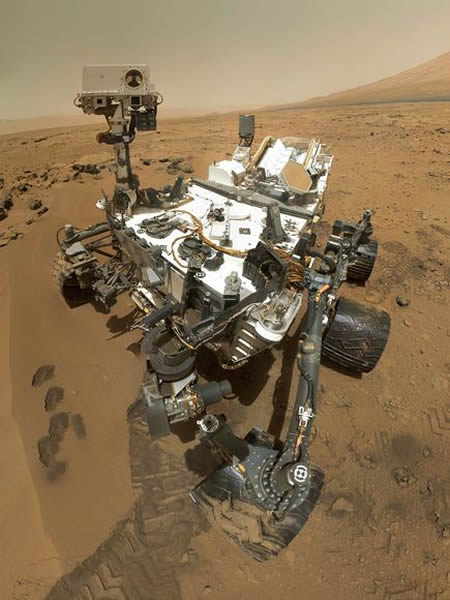

Curiosity's postcard from the Red Planet.

The now iconic self-portrait of the Mars rover Curiosity looks like someone, or something, other than the rover took its picture. The photograph, seemingly taken from afar, features an image of the entire vehicle at a site called Rocknest—with tire tracks below, Mount Sharp in the background, and clear scuff marks where Curiosity's arm had scooped up soil for analysis.

The answer to who snapped the rover's picture lies not with extraterrestrials but with the imagination of three men, precision robotics from 130 million miles away, days of planning on Earth, and a bit of artistic Photoshopping.

A video released last week by NASA illustrates the daylong rover gymnastics used to take the self-portrait. As the video shows, the camera lens was kept in one place as much as possible to minimize parallax—the seeming change in location of objects within the images caused by a change in camera position—while the arm went through its contortions.

Plans for Curiosity's self-portrait began last year when film director James Cameron and Mars camera wizards Michael Malin and Michael Ravine (of Malin Space Science Systems) started brainstorming ways to create striking and scientifically important new images from the substantial photo equipment onboard the rover. The three men initially met on a project to design a zoom video camera for Curiosity that was eventually cancelled.

"The idea for a self-portrait was pretty obvious, but figuring out how to do it was not," said Ravine. It required days of work at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) test bed to plan out the sequence of arm moves that would correctly position the camera. But once Malin Space Science Systems had the right order, rover drivers at JPL integrated the sequence into Curiosity's computer code.

Everyone's painstaking work ultimately produced a 55-frame sequence that captured everything they would need for the image.

Say Cheese

The actual photo shoot took place in October over two Martian days, known as sols, using the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI) camera, which sits in a turret at the end of the rover's nearly seven-foot-long (two-meter) arm. The camera is a stand-in of sorts for a geologist's magnifying tool, and it can focus on objects very far away, as well as up close (as near as 0.8 inches, or 2 centimeters).

Once the rover transmitted the images back to Earth, Ravine and a coworker set out to make a mosaic compilation of them. There were challenges galore, but none quite so great as getting the long arm of the rover out of the picture. A close look at the final image shows the "shoulder" of the robotic arm on the front of the rover. But the rest of the five-jointed appendage has been removed and replaced by pixels from other frames that showed the ground or the rover behind the arm.

"Actually, there weren't that many images with the arm in them because of how we positioned the arm," Ravine explained. "It's like if you hold a camera out in front of you with your elbow crooked and shoot—what you'll probably get is your face and top of your body including your shoulder, but most of your arm is out of the frame."

Camera Moves

The dance of the robot arm as it took photos for the mosaic was plotted by rover planners at JPL using 3-D visualization software that maps the terrain near the rover based on pairs of cameras on Curiosity. The rover planners used the same software—Rover Sequencing and Visualization Program—to generate the animation video of the robot's movements during the portrait session.

While the self-portrait is not currently in 3-D, it will be in the future. As conceived by Cameron, Malin, and Ravine, the picture-taking sequence was run on two successive days with the MAHLI position shifted by the distance between a typical person's eyes. This produced two self-portraits taken from slightly different angles. Brought together by 3-D glasses, the two images create the change in perspective needed for a 3-D image.

Given that MAHLI is primarily on Mars to help geologists examine cliffs, rocks, and sand, the researchers and engineers are as surprised as they are pleased that their scientific instrument has turned out to be such a good portrait camera too.

National Geographic News

Published December 5, 2012