ISON is Comet of the Year, Not the Century

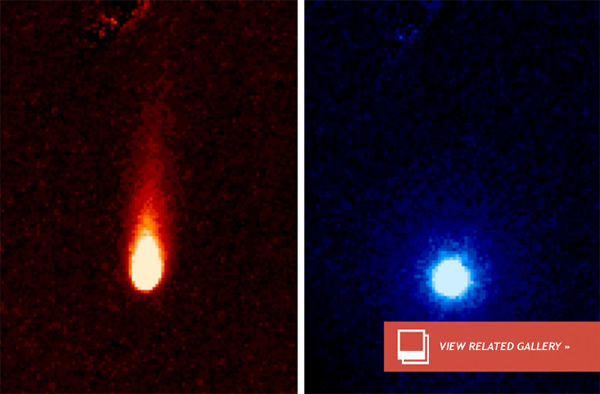

The countdown clock is ticking to comet ISON’s hair-raising passage around the sun on Nov. 28, as it grazes the sun at a distance of only 1.5 times the sun’s radius. Astronomers continue reworking estimates of how much of an impression the far visitor will make to Earthbound observers.

The prognostication is so chancy that I couldn’t even get comet-hunting veteran Mike A’ Hearn of the University of Maryland to give me an estimate of how bright it might get. When pressed for a guess, A’Hearn waved his arms and said ‘perhaps moderately bright,’ which would make the nucleus dimmer than the stars in the Big Dipper.

This led A’Hearn to dub ISON the “comet of the year” — not the century as earlier Internet chatter had suggested. It’s hard to believe that at the beginning of this year some astronomers were humming with speculation that the comet might become as bright as the full moon.

The excitement was built around the fact the comet is a first-time visitor to the solar system, fresh with virgin ices. Comet ISON was discovered in September 2012 by the International Scientific Optical Network located near Kislovodsk, Russia. But a search of archival data from the Pan-STARRS sky survey showed that the comet was bright enough to be photographed as early as 2011, but overlooked.

This means that it was detectable at a whopping distance of nearly 1 billion miles from the sun. When the rate of brightening was extrapolated from early 2013 to today, it showed the comet could get quite bright. But a few months ago ISON’s brightness rise flat-lined, and has now dimmed by one stellar magnitude.

But comets are notoriously unpredictable. Perhaps ISON will surprise us when it rounds the sun.

Some astronomers speculate that there is a 50/50 chance the fragile nucleus — which is roughly the density of polyurethane foam — will be ripped apart by gravitational tidal forces when it passes the sun. Sky watchers could be treated to seeing a decapitated lingering tail of the comet in the morning sky, absent of a glowing nucleus at the tip.

What has also been learned that raises some intrigue is that ISON is barreling head first toward the sun. Its rotation axis is pointed within 30 degrees of the sun, as first suggested in Hubble telescope photographs taken in April. This means the opposite hemisphere of the three-mile diameter nucleus has not seen sunlight for 4.5 billion years. But that will abruptly change in November as the comet rounds the sun and the shadow side is illuminated. Will this make it briefly flare up in brightness?

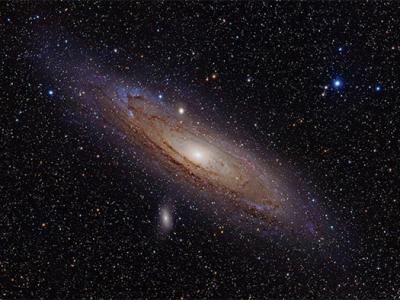

In 1950, Dutch astronomer Jan Oort studied the orbits of 18 comets to extrapolate that they came from a deep freezer reservoir of over 1 trillion comets located halfway to the nearest star. Despite the recent hoopla of Voyager 1 “leaving” the solar system, comet ISON has really never left the sun’s gravitational influence (nor has Voyager). For the past 5 million years it has been falling straight toward the sun on a bull’s-eye intercept.

The climax of this multi-millenium space odyssey is now just a few weeks away. If ISON survives the sun’s dragon breath, it won’t return again for another 12 million years. So grab your binoculars and catch it while you can!

Image credit: NASA(Sep 27, 2013 08:24 PM ET // by Ray Villard)