Wild Turkeys Invading Suburban U.S.

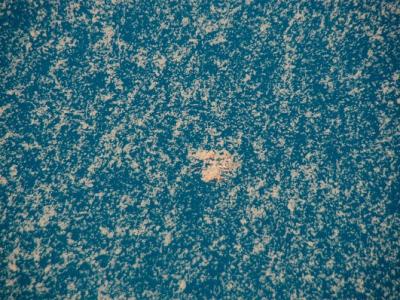

Wild turkeys cross a road in suburban Dover, Massachusetts, in November 2005.

Although the large birds had been hunted to near extinction in North America by the 1930s, reintroduction efforts since then have allowed the birds to resurge.

There are now nearly seven million wild turkeys roaming the United States—and they are unexpectedly thriving in urban and suburban settings.

Photograph by John Nordell/the Christian Science Monitor via Getty Images

Brian Handwerk

for National Geographic News

November 19, 2007

The Pilgrims found New England in the 1600s to be well stocked with wild turkeys, which figured into their regular diet, including the original Thanksgiving feast.

But by the 1930s the native birds had been hunted to near extinction in North America, numbering only in the tens of thousands.

Today, thanks to reintroduction efforts, there are about seven million wild turkeys, and they are thriving in an urban America that the early English settlers could not have imagined.

Wild turkeys have been spotted in towns and suburbs across New England—and have even been seen strolling through downtown Manhattan.

The turkeys' ability to take to these urban environments was a surprise to biologists.

"When restoration efforts started across the country, the rule of thumb was that turkeys required about 6,000 acres [2,430 hectares] of contiguous forest habitat," said Michael Gregonis, a wildlife biologist with the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

(Related news: "Country Owls Better Suited to the Suburbs?" [October 19, 2007].)

"We found that not to be true at all. Turkeys are pretty adaptable. As long as they have some cover and some trees that they can get up into at night to roost, they can do pretty well."

Who's the Boss?

Humans sharing space with the large, sometimes bold birds have mixed reactions.

"Some people look at them and say, How cool, and take a picture of them," said bird expert Chris Leahy of the Massachusetts Audubon Society.

"Other people look at them and say, Whoa, that's a big, scary bird."

"There was a case where I live [on Boston's North Shore] where some turkeys marched up onto a front porch and essentially kept a number of elderly women confined," Leahy continued.

"They were afraid to go out—though of course the turkeys had no intention of confining them anywhere."

Gregonis, with the Connecticut DEP, said that the birds have been documented in every one of the state's 169 towns, including a hen he chased at the downtown Hartford hospital.

When his phone rings, Gregonis tells nervous callers that there's no real danger and they should simply show aggressive birds who's boss.

"I have people harass the birds, pelt them with tennis balls or squirt them with a hose," he said. "If that's done enough, it will modify the bird's behavior" to leave you alone.

That's not to say that people should harass the birds when they are not being aggressive. In general, Gregonis stressed, conflicts are quite rare.

Connecticut boasts about 40,000 wild turkeys, but he gets just 15 to 20 calls about them a year, which tend to be clustered during the spring breeding season.

"A lot of this is young birds that try to establish their domain," he said. "They sometimes can get aggressive towards people. They jump up and flap their wings, and some people become intimidated by them."

James Earl Kennamer, of the nonprofit National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF), likens the behavior to that of a barnyard animal.

"I remember at my grandfather's farm the rooster would chase the little kids but wouldn't mess with the adults," said Kennamer, whose organization supports turkey conservation and hunting.

"They aren't going to hurt you. They're just trying to show that they are in charge."

This Land Is Whose Land?

Of course, the truth of the matter is that humans have been encroaching on turkey turf.

"In a lot of places turkeys have been there all along, but people are moving out to live in the woods and all of a sudden they are seeing turkeys," Kennamer said.

Mass Audubon's Leahy added that the birds are also behaving much as they always have.

"If you look at records going back to the Pilgrim [era], turkeys moved in large flocks and they were quite fearless—or clueless—and people could basically walk up to them and bop them on the head.

"Turkeys have not been particularly afraid of humans and have been readily accommodating to our habits and ways of living," he said.

"So it's not terribly surprising that we find them wandering in the suburbs or the streets of Brookline [in Massachusetts] and sort of catching meals where they can."

Particularly in suburban areas, ready supplies of free food also enable the birds to overcome any awe of humans.

"I think the big factor with these urban and suburban situations is the homeowner feeding turkeys," Connecticut DEP's Gregonis said.

"Over a period of time the birds get habituated to people, lose their fear, and actually tend to become more aggressive."

Ultimately such feedings harm the birds and may cause social strife in the human community.

"When you have somebody in the neighborhood that wants to feed them, and the rest of the neighborhood doesn't want them chasing someone in the driveway when they go to get a newspaper, it creates a dilemma," NWTF's Kennamer said.

Experts agree—if you see a wild turkey, enjoy the experience, but keep your snacks to yourself.

Wild Turkey Fast Facts

• The wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) was first domesticated by Native Americans. Spanish explorers took the birds to Europe in the 16th century, and the birds' tame descendents were brought back to the Americas with later settlers.

• Male turkeys, called toms or gobblers, weigh 16 to 24 pounds (7 to 11 kilograms). Hens are about half that size.

• Turkeys can run some 10 to 20 miles (16 to 32 kilometers) an hour and fly in bursts at 55 miles (89 kilometers) an hour.

• Turkeys roost in trees at night.

• Turkeys forage for many different foods, so a single suitable area can support a large flock without becoming depleted.

• Male turkeys (and a few females) grow beards that are about 9 inches (23 centimeters) long. Their tails, which they fan to attract females, are more than a foot (30 centimeters) long.