"Rogue" Dwarf Shines New Light on Tiny Galaxies

There's a new rogue dwarf joining our party—although it's not one you'd be likely to find in World of Warcraft.

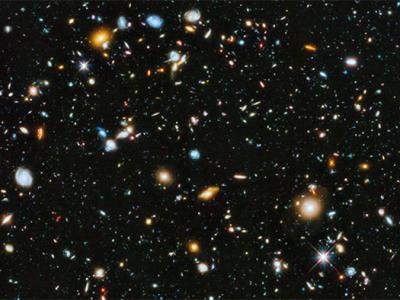

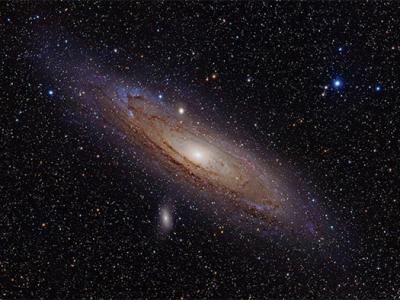

Andromeda XIV is a recently discovered dwarf galaxy on the outskirts of galaxy M31 (seen above), which is part of the so-called galactic local group that includes our Milky Way.

The odd dwarf is moving too fast to fit into standard models of how these tiny, faint galaxies take shape, a new study says, which suggests that it might have formed in isolation and is just now entering our cosmic neighborhood.

Image courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech

Scott Norris

for National Geographic News

November 21, 2007

A fast-moving "rogue" on the outskirts of the Andromeda galactic system may provide new insight into the nature of so-called dwarf galaxies and their potential role in galaxy formation.

The newly discovered dwarf, dubbed Andromeda XIV, may also indicate that the large spiral galaxy Andromeda—known to researchers as M31—is far more massive than had been thought.

Andromeda XIV is the latest in a number of recently discovered dwarf galaxies in the galactic local group, which includes our own Milky Way and its nearest spiral neighbor, M31.

Most of the previously known dwarfs in the local group are clearly satellites bound by gravity to the larger galaxies, researchers say.

But Andromeda XIV appears to be moving too fast to be locked in orbit around M31, said team leader Steven Majewski of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

For the new dwarf to be a satellite, M31 would have to be much more massive and exert a much stronger gravitational pull than current models suggest, Majewski said.

Perhaps more likely, Andromeda XIV may simply be a new arrival just entering our galactic neighborhood from distant regions of space.

"If Andromeda XIV is unbound to M31 and falling in for the first time, it would show that the assembly of the local group is not yet complete and that we are still picking up new members from outside," Majewski said.

A new arrival would give scientists a unique view of a dwarf galaxy in a relatively "pure" state, uninfluenced by billions of years of gravitational tug-and-pull with a larger neighbor.

Majewski's team—which also includes researchers at the University of California in Santa Cruz and Los Angeles—announced their discovery in a paper published this week in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Dark Building Blocks

Dwarf galaxies are so named because they contain only a few billion stars—a relatively miniscule number compared to the hundreds of billions of stars in galaxies like the Milky Way.

These tiny galaxies exist in a variety of shapes, with Andromeda XIV classified as a spheroidal dwarf.

Elliptical and spheroidal dwarf galaxies are thought to be composed almost entirely of dark matter, the mysterious, invisible substance that scientists believe makes up most of the mass of the universe.

"They're the most dark matter-dominated galaxies that we know of," Majewski said.

"In the case of Andromeda XIV we measure that 99.5 percent of the mass is dark matter—the luminous part is only a tiny fraction of the total."

(Read: "Universe's 'Missing' Matter May Lurk in Dwarf Galaxies" [May 11, 2007].)

Although their low luminosity makes them difficult to observe, other evidence suggests that dwarf galaxies are common throughout the universe.

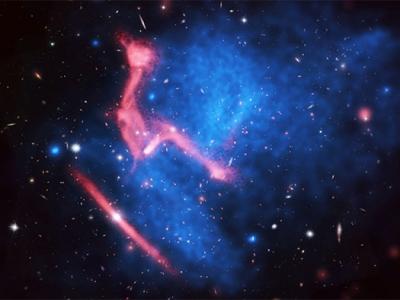

Current cosmological theory views dwarfs as galactic building blocks, which join together over billions of years to produce larger spiral galaxies.

Evidence of this process—galaxy formation by accretion—can be seen in surveys of the distant universe, Majewski said.

"You can see structures formed by the hierarchical merging of little things into ever bigger things all over the place on a larger scale," he said.

"Dark matter gathers together in filaments and moves along these filaments into the larger clusters of galaxies."

Scientists are unsure about the degree to which this process is occurring today. Until now, Majewski noted, there has been no direct evidence of such galactic infall occurring in the local group.

"Andromeda XIV could be solid evidence that the hierarchical formation of small galaxy groups is still happening—and happening as expected from theory—right in our backyard."

Splendid Isolation

Daniel Harbeck is an astronomer at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who was not part of the new study.

If Andromeda XIV is a new arrival to the local group, "it would be exciting and unexpected, and would provide hints about the formation of dwarf galaxies in isolated environments," he said.

More than 20 known or suspected dwarf galaxies exist as satellite companions to the Milky Way, and a similar number accompany M31.

Other dwarf spheroid galaxies lack gas and do not actively produce stars, characteristics that had been attributed to their long association with the larger spiral galaxies.

"The theory is they fell into a larger galaxy like the Milky Way, which then strips out their gases," lead study author Majewski said.

"But Andromeda XIV doesn't seem to have any gas either," he continued.

"If Andromeda XIV lived most of its life in splendid isolation, this would show that little dwarf galaxies can stanch their own [growth] by blowing out all of the gas necessary to make new generations of stars."

The question of whether the new dwarf is bound to M31 should be settled by further research, Majewski added.

Another astronomer, Daniel Zucker at the University of Cambridge in England, noted that Andromeda XIV may not be the only new arrival to the local group.

In a separate, recently published paper, a team led by Cambridge's Scott Chapman reported that another M31 dwarf, Andromeda XII, is also moving at high speed and may be approaching the larger galaxy for the first time.

"Speculation that these two dwarfs may be dynamically related is intriguing," Zucker added.