Oddest Couple Found in Fossilized Embrace

Oddest Couple Found in Fossilized Embrace

It’s the oddest, oldest couple ever found: a handicapped amphibian and a mammal-like reptile entwined in a 250 million year old embrace.

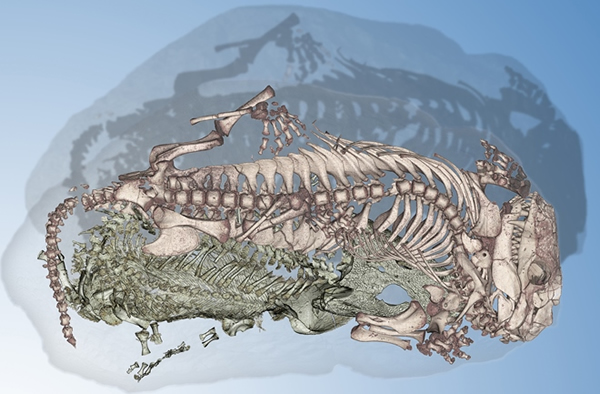

Fossilized after being trapped by a flash flood event, the unlikely pair was discovered following synchrotron X-ray scans of a lithified burrow cast from the Karoo Basin of South Africa.

“We were amazed by the quality of the images, but the real excitement came when we discovered a second set of teeth completely different from that of the mammal-like reptile,” study’s lead author, Vincent Fernandez, of Wits University, South Africa, said.

Surprisingly, the curled up skeleton of a sharp-toothed Thrinaxodon, a carnivorous reptilian ancestor to mammals, appeared huddled together with the juvenile skeleton of a Broomistega, a primary aquatic amphibian.

“The animals were buried with intact soft tissue, including the skin, and were possibly even alive,” Fernandez and colleagues wrote in the journal PLoS ONE.

The unique mixed-species association was dated to the beginning of the Triassic Period. At that time the ecosystem was recovering from the Permo-Triassic mass extinction that wiped out up to 96 percent of all marine species and 70 percent of terrestrial vertebrates.

To survive the harsh environment, many animals, including mammal-like reptiles, developed a digging behavior and burrowed into the earth for protection. Indeed, many Thrinaxodon specimens have been found in South Africa, fossilised in a curled-up position.

As for the Broomistega, the animal had quite serious reasons to crawl into the safe burrow.

The amphibian’s skeleton — the first complete one of this rare species — revealed the animal was suffering from broken ribs from a single, massive trauma to the right thorax.

As the partially healed fractures showed, the animal clearly survived the injury, but was quite handicapped and surely needed a safe shelter.

The position of the two organisms in the burrow suggest they were peacefully resting in the den at the time of death. The researchers investigated all possible reasons for such an unusual co-habitation.

“Burrow-sharing by different species exists in the modern world, but it corresponds to a specific pattern,” Fernandez said. For example, a small visitor is not going to disturb the host. A large visitor can be accepted by the host if it provides some help, like predator vigilance. But neither of these patterns corresponds to what we have discovered in this fossilised burrow.”

The researchers ruled out the accidental hypothesis because the small diameter of the Thrinaxodon burrow “effectively excludes the possibility that the relatively large Broomistega was randomly washed in by a flood event,” they said.

A prey-predator relationship was also rejected as both skeletons are almost fully articulated and undisturbed, “meaning it is implausible that one may have fed on the other,” the researchers concluded.

As strange as it may seem, it appears that the Thrinaxodon tolerated the presence of the amphibian intruder.

The researchers believe the Thrinaxodon was most probably aestivating in its den. Along with burrowing behaviour, this key adaptation response allowed some species to survive the Permo-Triassic mass extinction event.

“This state of torpor explains why the amphibian was not chased out of the burrow,” Bruce Rubidge, director of the Palaeosciences Centre of Excellence at Wits, said.(Jun 24, 2013 12:07 PM ET // by Rossella Lorenzi)