Creating a New Map of the Holocaust

The map of the Third Reich is being dramatically redrawn.

Thirteen years ago, when he started digging into the past to document the number and nature of Nazi-era ghettos and camps, scholar Geoffrey Megargee expected to identify perhaps 7,000 sites. He vastly underestimated his task. More than 42,200 sites will be named in the planned seven-volume encyclopedia that he is editing: The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945.

This week is Holocaust remembrance week in the United States, with an official ceremony at the U.S. Capitol Rotunda on April 11 at 11 a.m. For the latest insights into the Nazi era, we spoke with Megargee and Martin Dean, editor of volume two of the encyclopedia: Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe.

"To document this on a map and see how the Holocaust affected every single community throughout Europe makes quite clear the scope of the Nazi regime's murder campaign," says Dean.

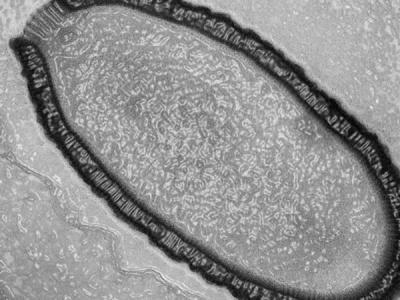

SS guard Schmiller walks past the barn of the Lipa farm labor camp where Jewish workers pitch hay.

Investigating the Sites

To be included in the encyclopedia, a site had to have housed at least 20 people and have been in existence for at least a month. In addition, it had to have been identified on a map—not the easiest thing to do when some towns in question have changed their names several times since World War II ended.

The scholars drew upon past research and interviews with survivors but also sought records that have "disappeared into archives in a dozen different countries," says Megargee. Many of the archives were behind the Iron Curtain until the 1990s, off limits to outside scholars. Even now some are restricted.

The sites include the extermination camps where gas chambers were built for "the final solution" of murdering the Jewish people. But that's only part of the project's scope.

"We're not just looking at sites directly involved with the Holocaust," says Megargee, "but [also] with the entire range of persecutory facilities that the Nazis and their allies ran."

Forced Laborers Everywhere

Each listing has a careful yet hair-raising description of the site, drawing from records as well as survivor testimony. Many of the encyclopedia entries were forced labor camps.

"Think of what life was like in Germany," Megargee says. "There were foreign forced laborers in every conceivable kind of business: farms, factories, retail shops, hospitals, railroads. You couldn't go anywhere in Germany without encountering people being held against their will and forced to work. Their rights were being violated."

And it would have been no secret to German citizens that these laborers were in their midst. "Even in a large city, you know who lives in your neighborhood—and who doesn't," Megargee says. "And you could see barracks where these forced laborers lived."

Workers thought to be shirking their duties were sent to work education camps. They faced up to eight weeks of very hard labor along with beatings and possibly solitary confinement. If there was evidence of a change in behavior, the worker could go back to the forced labor camp. If not, he or she might be sent to a concentration camp.

The Work Education Camp Watenstedt-Salzgitter, established "in some woods just to the northeast of Hallendorf" in Germany, could hold about 800 female prisoners and 1,000 males at a time. The Encyclopedia entry mentions 492 documented deaths there in 1942 attributed to "weak heart" or "shot while trying to escape." A survivor of the camp recalls an SS man "who beat the prisoners on their way to breakfast." (There were Jewish inmates at this camp, but in most forced labor and work education camps in Germany, the internees were typically non-Jewish Europeans.)

Staggering Death Rate

Megargee says some of the categories of sites he found were "particularly surprising or horrible." The so-called Care Facilities for Foreign Women and Their Children were essentially holding pens for female workers, typically from Eastern Europe, who had become pregnant. At an earlier stage in the Nazi regime, these women would have been sent home to have the child. After 1943, they were sent to the Care Facilities, where "the baby was either aborted or, after birth, would be killed by slow starvation," says Megargee.

European Jews were first confined to ghettos. When the ghettos were shut down, most Jews were killed; only a few were selected for work and sent to forced labor and concentration camps, where they again were periodically selected to continue working or to be killed. The death rate for European Jews in the camps and ghettos was a "staggering" 90 percent, compared with 10 percent for the foreign workers held in German forced labor camps, Dean notes.

The Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos pays tribute to those many millions imprisoned and slaughtered by the Nazis by its memorialization of all the site names. On its pages a reader will find camps that few people have heard of, like the work camp at St. Martin's Cemetery in Poznan, Poland, where Jews had to excavate Polish graves to look for gold teeth, jewelry, or brass, and even smash up the headstones for the Nazi war effort. And there are the infamous names etched in the world's memory, like Auschwitz-Birkenau with its gas chambers.

"This is giving recognition to all of the thousands of places where people suffered and died," says Martin, "that would otherwise fade from people's consciousness."

Marc Silver

National Geographic News

Published April 8, 2013