Earth-Like Worlds "Very Common"

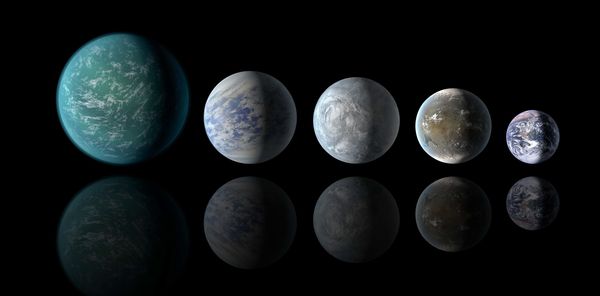

Shown are the relative sizes of all of the habitable-zone planets discovered to date alongside Earth. Left to right: Kepler-22b, Kepler-69c, Kepler-62e, Kepler-62f and Earth (except for Earth, these are artists' renditions).

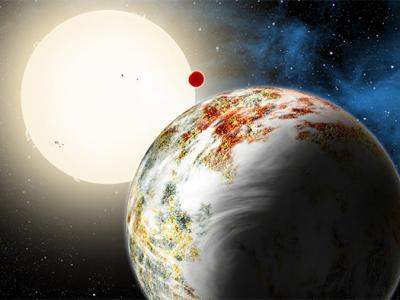

One in five sunlike stars harbors an Earth-size world that orbits in a "habitable zone" friendly to oceans and perhaps life, a new study suggests.

The findings, detailed in this week's issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, are based on a statistical analysis of observations made by NASA's now-crippled Kepler space telescope.

The astronomers estimate that 22 percent of sunlike stars may be orbited by small, rocky planets that reside within so-called habitable zones, where they receive Earth-like levels of sunlight.

"Our results show that small planets, with sizes similar to our Earth, are very common,” said study leader Geoffrey Marcy, an astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley.

What's New?

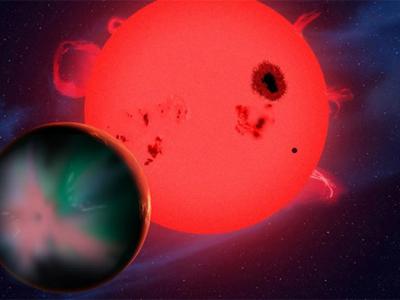

Launched in 2009, Kepler was tasked with finding alien planets, or "exoplanets," by looking for the telltale dimming of light that occurs when a world passes in front of, or "transits," its parent star.

For four years, until its malfunction this summer, Kepler stared at 150,000 stars situated in a patch of sky in the direction of the constellations Cygnus and Lyra.

Out of that group, Marcy and his colleagues Andrew Howard and Erik Petigura, focused on 42,000 stars that are like our sun or slightly cooler and smaller.

The team found 603 potential planets, or "planet candidates," orbiting these stars. Ten of these were Earth-size, that is, one to two times the diameter of Earth and orbiting their star at a distance where they are heated to lukewarm temperatures thought amenable for life.

The team next introduced 40,000 fake planets into the Kepler data as a test for their analysis software.

The fake planets ranged from Earth-size to ten times the size of Earth. They also had a range of orbital distances: Some were located within the habitable zone, while others were either too close or too far from their star.

Similarly, the team accounted for missed planets in their analysis, as well as the fact that only a small fraction of planets follow orbits that allow their crossings in front of their host star to be seen from Earth.

Overall, the team estimated that 22 percent of all sunlike stars in the galaxy have Earth-size planets in their habitable zones.

Why Is It Important?

The findings could also have implications for planet-formation theories that attempt to explain how different varieties of planets form in the ratios that they do, Marcy notes.

"People who construct theories about the formation of planets can now use our results to build computer models that simulate the formation processes of planetary systems," he said.

"They now have touchstones to test their theories. The theories must 'predict' the observed plethora of, and orbits of, Earth-size planets that we actually observe in the universe."

What Does This Mean?

The results also suggest that the nearest Earth-like alien world could be as near as 12 light-years away—close enough to be seen with the naked eye.

"Astronomers know the locations of all the thousands of stars near our solar system. Now we know that one in five sunlike stars has an Earth-size planet in the habitable zone," Marcy said in an email.

"You can imagine traveling outward from our solar system, stopping at the nearest sunlike star, then stopping at the second nearest, and so on. When you arrive at the fifth, you have passed five sunlike stars. On average, one of those five sunlike stars has an Earth-size planet in its habitable zone, with lukewarm temperatures, suitable for life."

That number could prove really important for NASA and other space agencies planning follow-up missions to Kepler, said study co-author Howard, a former UC Berkeley post-doctoral fellow who is now on the faculty of the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii.

"Successor missions to Kepler will try to take an actual picture of a planet, and the size of the telescope they have to build depends on how close the nearest Earth-size planets are," Howard said in a statement.

What's Next?

Now that they have an idea of what the abundance of habitable worlds in our galaxy is, Marcy and his team are planning an audacious next step.

"We will point the world's largest telescopes at the Earth-size planets, trying to receive the laser communications sent by any intelligent civilizations that live on those planets," he said.

"We will probably fail. But if we don't try, we will surely not detect them."

Ker Than

For National Geographic

Published November 4, 2013