Russian Meteor's Air Blast Was One for the Record Books

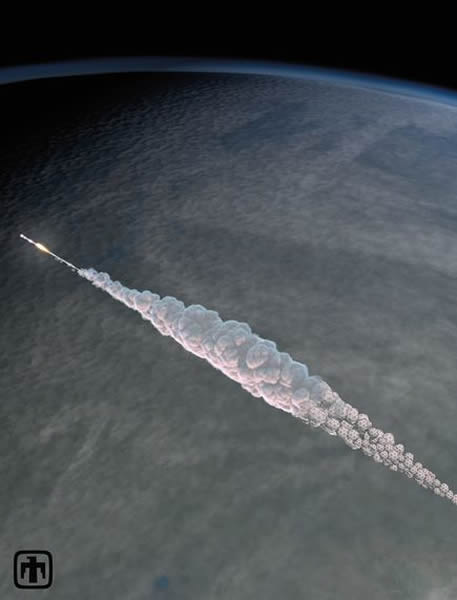

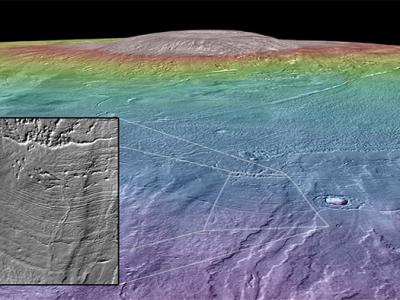

This 3-D simulation of the Chelyabinsk airburst shows the immense power of the meteor's air blast, the strongest to hit Earth in a century.

The February meteor blast over central Russia glowed 30 times brighter than the sun, sunburned observers, and delivered the biggest astronomical punch felt on Earth in a century, report scientists.

Scientists warn that the 500-kiloton-or-stronger "airburst" over Chelyabinsk on February 15, 2013, points to a higher-than-expected threat from similar small asteroids in the future.

Published by the journals Science and Nature, the three related analyses combine data from satellites, seismometers, dashboard cameras, damage surveys, and asteroid fragments to look at the Chelyabinsk event.

In the studies, the international impact teams re-created the roughly 65-foot-wide (20-meter-wide) asteroid's 42,500 mile-per-hour (68,400 kilometer-per-hour) collision with Earth's atmosphere.

The event injured about 1,500 people and damaged thousands of buildings in a part of central Russia that is home to one million people.

"Some witnesses reported being burned by the light," says Science study co-author Peter Jenniskens of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California.

"Not just the windows were broken, but the window frames were pushed in, in the buildings," said Jenniskens in a Science podcast. "The [shockwave] was so strong that it was able to topple over people standing."

Meteor Surprise

On the day of the meteor's arrival, much of the astronomical world's attention was turned toward 2012 DA14, an office-building-size asteroid that made a close 17,100-mile-high (27,520-kilometer-high) passage over Earth.

News of the Russian meteor took observers by surprise, although experts such as NASA's Bill Cooke quickly deduced that it was unrelated to 2012 DA14, which passed harmlessly over the South Atlantic. Instead, the Chelyabinsk meteorite started its 18-second death plunge heading east across central Russia, in the Northern Hemisphere.

Astronomers didn't see it coming because of its relatively small size and because it was hurtling toward our planet from a sun-facing direction, blinding telescopes.

On its trajectory, the meteor first created a shock wave in the air about 59 miles (95 kilometers) above Earth, growing in strength and brightness as it burned and began to fragment.

At about 17 miles (27 kilometers) high, it broke apart, according to the Nature study led by Peter Brown of Canada's University of Western Ontario.

The breakup delivered a final blast of air pressure felt within 79 miles (127 kilometers) of the meteor.

Shattered fragments rained across central Russia, and a hole 23 to 26 feet (7 to 8 meters) wide was punched in the 27-inch-thick (70-centimeters-thick) ice of Lake Chebarkul, near Chelyabinsk. A 1,300-pound (600-kilogram) meteor fragment was recently recovered from the lake.

Meteorite Origins

One Nature study led by Jiri Borovicka of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic ties the Chelyabinsk meteor's trajectory to rubble from the near-Earth asteroid 1999 NC43, which is roughly 1.37 miles (2.2 kilometers) wide and orbits the sun on a path that crosses Earth's orbit every few years.

Asteroid 1999 NC43 is not itself seen as a threat to Earth, but one of the analyses suggests that something hit the asteroid perhaps 1.2 million years ago, knocking off pieces of rubble that included the Chelyabinsk meteor.

"The rest of the rubble could still be part of the near-Earth object population of asteroids," concludes the Science study led by Olga Popova of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow.

That means more pieces could be headed our way.

Airburst Threat

That same concern appears in the Nature analysis led by Brown, which notes that only about 500 asteroids in the size range of 33 to 66 feet (10 to 20 meters), the size range of the Chelyabinsk meteor, have been spotted by astronomers to date.

But perhaps 20 million such small asteroids are thought to orbit on paths that bring them near Earth, the authors say.

That significantly raises the possibility of future airburst events like the Russian meteor, the study suggests, and the 1908 Tunguska event.

Tunguska was a much larger, 10,000- to 50,000-kiloton airburst that flattened several hundred miles of Siberian forest (for context, the 1945 atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima delivered a roughly 15-kiloton explosion).

"Chelyabinsk opens the door for new analyses of airburst events and their frequency," says MIT impact expert Richard Binzel, who was not on the study teams. He calls the studies a "final word" on the much-debated size and power of the Russian meteor.

Dan Vergano

National Geographic

Published November 6, 2013