Manned Mission to Largest Known Asteroid Designed

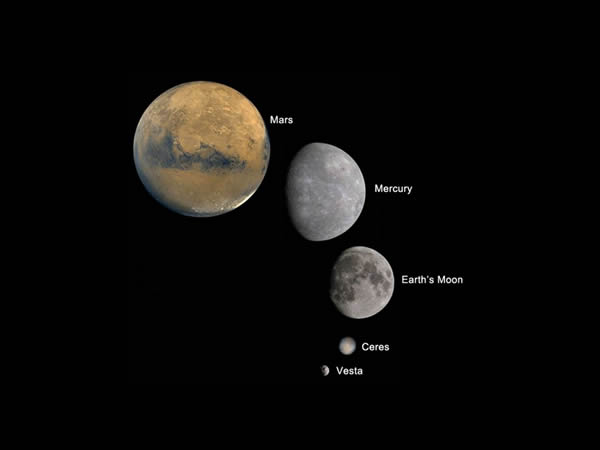

Ceres is shown in relation to Vesta, Earth's moon, Mercury, and Mars in an illustration.

Rocket scientists who have plotted a course for a human mission to the largest known asteroid, Ceres, say that such a voyage may not be much more challenging than sending people to Mars, according to a new study.

Research investigating human missions to asteroids blasted off in 2010, when President Obama proposed a human mission to an asteroid by 2025. NASA's Asteroid Initiative plans to use a robotic spacecraft to tow an asteroid to a stable orbit just beyond the moon, which would enable astronauts to visit the space rock as soon as 2021.

However, "we wanted to look beyond the small asteroid that President Obama's plan wants to send people to," said aerospace engineer James Longuski of Purdue University in Indiana. "Let's take a bigger step to the biggest asteroid."

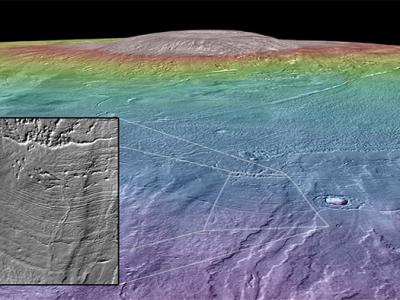

Ceres was the first asteroid discovered, and is roughly 605 miles (975 kilometers) wide, or as big across as Texas. This makes it the largest asteroid in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter—it accounts for more than a third of the belt's mass.

"It's so large, it has enough of a gravitational field to pull itself into a round shape, unlike most other asteroids, which just look like potatoes and funny-shaped rocks," Longuski said.

Ceres is also the smallest and closest dwarf planet at about 257 million miles (415 million kilometers) from the sun, and is the only one in the inner reaches of the solar system. NASA's Dawn spacecraft is scheduled to reach Ceres in 2015.

Intriguingly, Ceres may have vast amounts of frozen water beneath its crust—if it was composed of 25 percent water, it would have more water than all the fresh water on Earth. Some researchers even think Ceres may have an ocean of liquid water under its surface, potentially making it of interest to scientists looking for signs of extraterrestrial life, since there is life virtually wherever there is liquid water on Earth.

"There's also a lot we could learn about the birth of the solar system from Ceres, since it's essentially a large leftover from the solar system's formation," said aerospace engineer Frank Laipert, also of Purdue University. "And a human could be a lot more effective as a scientist on Ceres than a robotic probe."

Going Nuclear

Longuski and Laipert calculated the best, most efficient way for humans to fly to Ceres would be with engines that electrically thrust out matter for propulsion.

The team calculated that nuclear power is a better source of electricity than solar for such propulsion for this mission because it weighs less and can provide the constant power needed for continual thrust to Ceres.

In their design for a human mission to Ceres, the scientists limited the crew time spent on the asteroid-bound and Earth-bound legs of the mission to 270 days each and the total crew time spent away from Earth to two years. Their aim was curbing astronaut exposure to hazardous deep-space radiation, which can cause cancer.

Unlike Mars, Ceres' gravity is too weak to help capture any spacecraft hurtling toward it. Moreover, it has no atmosphere to help slow down a lander. As such, any mission to the dwarf planet needs a substantial amount of propellant to get close to the asteroid and then brake its approach.

The researchers divided the flight to Ceres into three parts. First, a supply vehicle would arrive at Ceres, bringing all the supplies needed to sustain the crew while on the asteroid as well as any equipment and propellant required to return to Earth.

Next, the crew vehicle is assembled in low Earth orbit and travels in elliptical spirals away from Earth. However, it travels without astronauts on board for about two years, to limit crew exposure time to deep-space radiation.

Finally, once the massive spacecraft builds up enough speed to reach Ceres, the astronauts take a small capsule to rendezvous with the crew vehicle and fly to the asteroid.

"As Easily as Mars"

All in all, the scientists calculated the crew mission would need an initial mass of 289 metric tons and the supply mission 127 metric tons, or 458 metric tons combined.

In comparison, the International Space Station weighs about 450 metric tons. The researchers said four heavy-lift rockets would suffice to carry the entire mission into orbit, comparable with what current plans for a human mission to Mars require.

"We can go to Ceres as easily as Mars," Longuski said.

The key technology that a human mission to Ceres needs to develop is a nuclear power plant capable of generating nearly 12 megawatts of power.

"It's probably the most futuristic piece of technology we relied on for our study," Laipert said. A mission could be feasible with just a 8- to 9-megawatt system, although more propellant would be required, he added.

The researchers noted that better, more efficient trajectories to Ceres may exist, such as ones using the moon's gravity to slingshot a spacecraft outward. They also noted the water on Ceres could be electrically split apart into hydrogen and oxygen for propellant, potentially cutting down the amount of supplies the mission needs to deliver to the asteroid.

Still, the investigators said that even without these options, their work demonstrated that a human mission to the dwarf planet was feasible.

The investigators suggested the supply missions could begin launching in October 2026, with the crew mission departing in August 2030 and returning in May 2032. Launch opportunities should repeat about every 2.3 years, according to the study, published online November 2 in the journal Acta Astronautica.

Speedy and Efficient

"They've identified a relatively speedy and efficient way to get people to Ceres and back," said planetary scientist and former NASA astronaut Tom Jones, a senior research scientist at the Florida Institute of Human and Machine Cognition, who did not take part in this study.

"It could be a part of an exploration plan after we go to Mars and want to expand farther out in the solar system."

Still, Jones did not see any reason for a human mission to Ceres. A robotic lander using the trajectories to Ceres that Laipert and Longuski developed "will likely tell us all we need to know about Ceres without the cost and risks of a human mission deep into the asteroid belt," Jones said.

By Charles Q. Choi

National Geographic

Published November 18, 2013