Mars Rover Finds Ancient Life-Supporting Lakebed

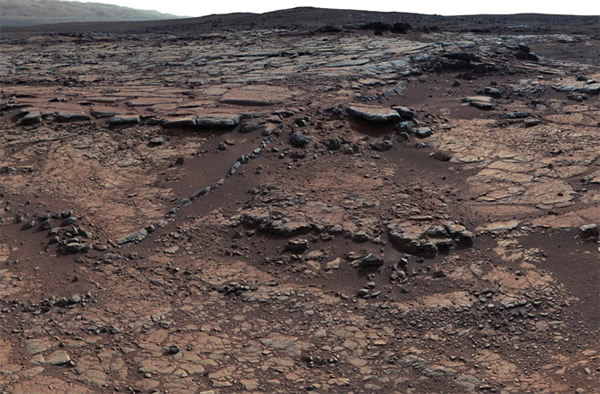

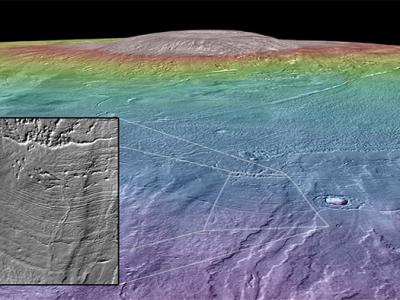

This mosaic of images from Curiosity's Mast Camera (Mastcam) shows geological members of the Yellowknife Bay formation, and the sites where Curiosity drilled into the lowest-lying member, called Sheepbed, at targets "John Klein" and "Cumberland."

The site where NASA’s Mars rover Curiosity landed last year contains at least one lake that would have been perfectly suited for colonies of simple, rock-eating microbes found in caves and hydrothermal vents on Earth.

Analysis of mudstones in an area known as Yellowknife Bay, located inside the rover’s Gale Crater landing site, show that fresh water pooled on the surface for tens of thousands -- or even hundreds of thousands -- of years.

“The results show that the lake was definitely a habitable environment,” Curiosity lead scientist John Grotzinger, with the California Institute of Technology, told Discovery News.

The really big surprise, however, was that clays drilled out from inside two mudstones and analyzed by the rover are much younger than scientists expected, a finding that extends the window of time for when Mars may have been suitable for life.

“These numbers now overlap with the oldest rocks on Earth that contain evidence of a former biosphere on Earth,” Grotzinger said.

The rover explored Yellowknife Bay before heading toward a three-mile high mountain of layered sediments rising from the floor of Gale Crater known at Mount Sharp.

Curiosity landed in August 2012 to assess if Gale Crater had the right ingredients and environments to support ancient microbial life. Within six months, scientists had the answer to that question: Yes.

Now, in addition to characterizing specific potential habitats, scientists are coming up with a search strategy to determine which sites hold the most promise for finding organic carbon, a far more difficult and complex challenge and the focus of future studies at Mount Sharp.

“Habitability only requires that the chemicals and minerals in the rock preserve evidence of an ancient environment. To search for organic carbon you’re actually looking for particular material ... that is not really compatible with the present environment of Mars. To find something you need a guidebook, you need some rules,” Grotzinger said.

One of those rules involves how much radiation a rock has been exposed to. Mars today has only has a thin atmosphere and no protective magnetic field, so scientists have been thinking they will need to dig deep to find carbon-laced samples, or they will have to probe craters relatively recently excavated by an impact.

Analysis of the Yellowknife Bay rocks points to another path. Dating the ages of the rocks’ surfaces show they are as young as about 70 million years, the result of being sand-blasted by Martian winds.

“In the future, if we find a rock that looks like a place where organics were accumulating and if it looks like the chemistry would have been favorable for preservation ... we can now very deliberately manage the risk that the rock would have been cooking away in the presence of radiation for hundreds of millions of years by looking for these scarps, these miniature cliffs, and then drilling the rock and date it to see how long it’s been laying around,” Grotzinger said.

In related research, scientists found that the amount of radiation measured by Curiosity during its first year on the Martian surface is about 40 percent of what the rover experienced during its nine-month cruise.

Most of the reduction, as expected, is due to the planet’s body serving as a buffer, but scientists also found that solar activity is a key factor, said Cary Zeitlin at Southwest Research Institute.

Six papers on Curiosity’s new findings are published in this week’s journal Science and unveiled at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco.(Dec 9, 2013 12:00 PM ET // by Irene Klotz)