Earliest Blooms Recorded in U.S. Due to Global Warming

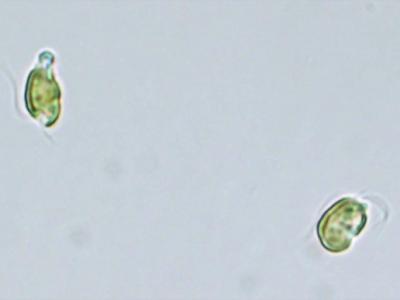

Forget-me-nots bloom during springtime (file picture).

You could call them early bloomers: In 2010 and 2012, plants in the eastern U.S. produced flowers earlier than at any point in recorded history, a new study says.

This result, according to the research team, has a bit of a literary twist: It comes from data collected by U.S. environmental writers Henry David Thoreau and Aldo Leopold. Thoreau began observing bloom times in Massachusetts in 1852, and Leopold began in Wisconsin in 1935.

Scientists compared this historical data with modern, record-shattering high temperatures in Massachusetts and Wisconsin during 2010 and 2012.

They discovered that those two recent warm spells triggered many spring-flowering plants to blossom up to 4.1 days earlier for every 1.8-degrees Fahrenheit (degree Celsius) rise in average spring temperatures.

Many studies have already shown that flowering times have come earlier as a result of recent global warming, but what's unknown is how long the plants will be able to "keep up" by budding earlier and earlier.

So far, plants—at least in the eastern U.S.—are coping.

"It's just remarkable that they can physiologically handle this," said study leader Elizabeth Ellwood, a biologist at Boston University in Massachusetts.

But Ellwood suspects that "at some point this won't be the case anymore as winter gets shorter."

"Something's gotta give."

Springing Forward

For instance, plants need to flower to reproduce. And in order to flower, they need a trigger—which is usually a long winter chill.

But if winters keep getting milder, plants may not get cold enough to realize the difference when warmer springtime temperatures start, noted Donie Bret-Harte, a plant ecologist at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

The concern is whether plants are "going to be able to adapt fast enough as climate changes radically, [or] is there some physical limit against which you're going to bump up [so] that you can't adapt any longer?"

For instance, Bret-Harte, who works in Alaska's Arctic, has already found evidence that Arctic plants are not doing well in warming temperatures. What's more, as northern climates warm, more southern species are marching northward where they may outcompete native species.

Another worry is that plants will flower early and a late-winter freeze will destroy the buds, Bret-Harte added.

That will likely weaken the plant, though not kill it outright, noted study leader Ellwood.

Early blooming also "has tremendous implications" for the environment as a whole, she said.

Since plants soak up and evaporate water, as well as take in carbon dioxide during photosynthesis, they can influence our planet's water cycle and atmosphere. For instance, more evaporation may mean more cloud cover, which in turn could affect rainfall.

So if you take "one plant times a million plants, you could see how atmosphere or water cycle could be affected by plants flowering earlier," said Ellwood.

"A Natural Resurrection"

Though not a breakthrough, the study is "a nice illustration of extreme events" that many scientists have been observing, noted This Rutishauser, a climate scientist at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

But he pointed out that the study would have been stronger if it had included data on winter temperatures before 2010.

According to the study, plants in Massachusetts and Wisconsin predictably flower when temperatures change. But if the study researchers had found, for instance, that winters before 2010 were extremely warm and that the plants were still able to flower come springtime, then that would present a "much more complicated story," Rutishauser said.

He added the study's publication is merited by drawing on "famous observers" Thoreau and Leopold.

Though we don't know what Thoreau would have said about spring arriving earlier in his native Massachusetts, he was certainly a fan of the season.

Spring, he wrote in 1852, "is a natural resurrection, an experience of immortality."

The early-flowering study was published January 16 in the journal PLoS ONE.

Christine Dell'Amore

National Geographic News

Published January 16, 2013