“Lazy” Algae Freeload Off Toxic Kin

No such thing as a free lunch? That may not be the case for a certain strain of single-celled algae, a new study says. The microscopic organism is apparently even lazier than normal algae, which never made our list of most industrious organisms to begin with.

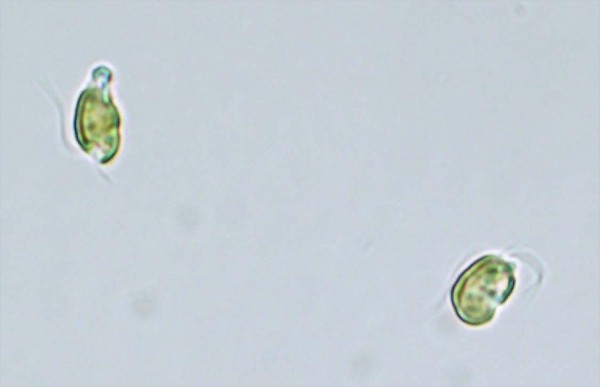

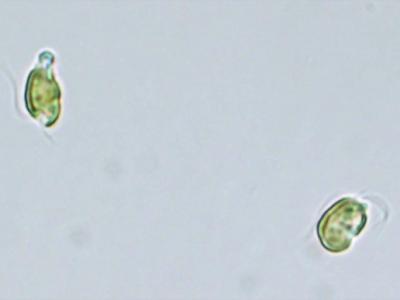

Prymnesium parvum, a distant cousin of phytoplankton and giant kelp, is typically found in the ocean. Occasionally, certain conditions—such as an increase in nutrients in the water—can spur the algae to reproduce rapidly, causing harmful “blooms” that can be toxic to ecosystems. P. parvum has also recently bloomed in freshwater environments, where they’ve had devastating effects, such as fish kills.

Upon examining several strains of P. parvum—also known as “golden algae” due to metallic-looking pigments—biologists at the University of Arizona have discovered that while most members of an algal bloom produce a defensive toxin, certain strains do not.

While their cohorts in the algal bloom are busy producing toxins to ward off competitors or attack prey, the freeloading floaters just enjoy the ride, dedicating precious resources toward other functions such as accelerated growth and reproduction—all while benefiting from their fellow microbes’ hard work. They go on the road trip without chipping in for gas, so to speak.

“When those ‘cheaters’ are cultured with their toxic counterparts, they can still benefit from the toxins produced by their cooperative neighbors—they are true ‘free riders,’” study leader William Driscoll said in a statement.

Algal Free Riders See Short-Term Benefit

What has researchers puzzled is how the lazy behavior evolved and why it hasn’t taken over, since it seems to confer an advantage.

Golden algae is seen in a microscopic image. Picture courtesy of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

“Producing toxins only makes sense if the entire population does it,” said Driscoll, whose study recently appeared in the journal Evolution. “Any given individual cell won’t get any benefit from the chemicals it makes because they immediately diffuse away. It’s a bit like schooling behavior in fish: A single fish can’t confuse a predator—you need everyone else do the same thing.” (See marine-microbe pictures.)

One theory is that toxic and nontoxic algal strains evolved for different aspects of the boom-and-bust cycle that algae go through, since the toxins are useful when attacking prey during an algal bloom but less useful afterward, when most prey has been eliminated.

Driscoll drew an analogy with cancer cells, which can “thrive” short term but threaten the health and survival of the system in the long term.

“What we may be seeing in our algae is a—far less extreme—version of a similar story, because a short-term advantage to not producing toxins may interfere with the long-term competitive ability of the population,” said Driscoll.

The microscopic moochers may yet redeem themselves however. Scientists speculate that learning more about the genes that account for switched off toxicity could yield new ways of combating toxic algae blooms that have devastated fisheries.

Who says cheaters never prosper?

Stefan Sirucek is a writer, journalist, and map enthusiast. His work has appeared in the Huffington Post and the Wall Street Journal.

Posted by Stefan Sirucek in Weird & Wild on January 22, 2013