Great Barrier Reef: Through the Lens of David Doubilet

A marine scientist admires a garden of stony corals.

Underwater photographer David Doubilet made his first trip to Australia's Great Barrier Reef in 1979. Since then, he's returned 11 times to the 1,400-mile-long (2,254-kilometer-long) kingdom of coral off the Queensland coast.

In light of news that the United Nations may add the reef to the list of endangered World Heritage sites, editor at large Cathy Newman spoke to Doubilet about his encounters with the reef and its uncertain future.

You've made 12 trips to the Great Barrier Reef over the past three decades. What do you remember about your first trip?

I had my first encounter with a sea snake. A big olive-green one came up and got between my buoyancy compensator vest and neck and looked me in the face. They are very poisonous. In Australia everything is out to get you. I held my breath, very carefully loosened the vest, and the snake slithered out.

Let's try for another experience of a less terrifying nature.

Raine Island, which is off the Cape York Peninsula, is the jewel of the reef. Every other year it hosts 80,000 green turtles that come to mate and crawl on the island and lay eggs. I went with a scientist who had a permit to work there and swam with hundreds of turtles that moved like underwater clouds. They seemed to appear and disappear because they blend in perfectly with the surrounding reef. Such numbers in one small place makes them very vulnerable. Ten thousand plus turtles would pull themselves ashore at night. It was the Times Square of green sea turtles. As dawn broke, the last females were pulling themselves toward the sea. The island was covered in tracks that looked like a massive amphibious landing. I have never seen anything like it.

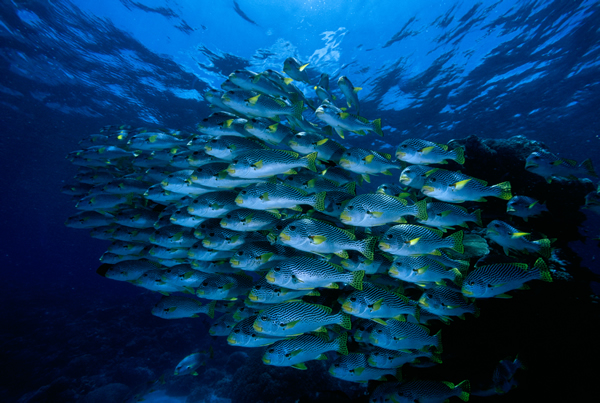

A school of Sweetlips fish in the Great Barrier Reef.

What's it like to work on the reef?

The reef is a long way offshore, and the wind blows. It's not easy to get at. You don't land in Sydney and take your swim fins and swim out. You have to go to Cairns way up the coast and take a boat and ride for hours. (Watch video: David Doubiliet's Underwater Photography.)

What's changed since you first went there?

The biggest single change is how people are using the reef. It came about with the development of high-speed catamarans that could take you out to the reef for the day. The reef has become insanely popular.

The clownish grin of a bridled parrotfish, one of the many fish that live in Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

Has that impacted the reef adversely?

Not as much as other things. The greatest danger is the rising temperatures of climate change.

What else?

There are many threats—ocean acidification and outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish [a coral polyp predator]. As we look at the reef we discover more and more problems. Development, industry, and port traffic is increasing along the coast. A lot of coal is coming from the interior and being shipped out. So there are big ships going through the reef. A few years ago a bulk coal carrier was shipwrecked on the reef out of the port of Gladstone.

That was the Chinese bulk coal carrier the Shen Neng 1 that tore a two-mile-long scar in the reef and leaked oil. What can be done about the risks posed by shipping traffic?

Well, you can say you can't build more coal terminals. But that isn't going to happen. That's where the money is.

What does the future hold?

It's not an easy question to answer. The reef is so vastly complex. [Writer] Doug Chadwick calls it "a nation offshore." Whether it disappears or changes into something we don't know is as yet unknown. Charlie Veron, a longtime chief scientist for the Australian Institute of Marine Science, says much of the reef will be nearly bereft of life within 50 years.

Why is this important? What relevance does it have to, say, the guy living on a lake in New Hampshire?

Reefs are the tropical thermometers of the health of the planet. The change is longer in term; it's not like the sea ice that you can see melt. The person living in New Hampshire may not be immediately affected. But it will indicate what will happen eventually. Climate change is in your face.

Cathy Newman

National Geographic

Published June 8, 2013